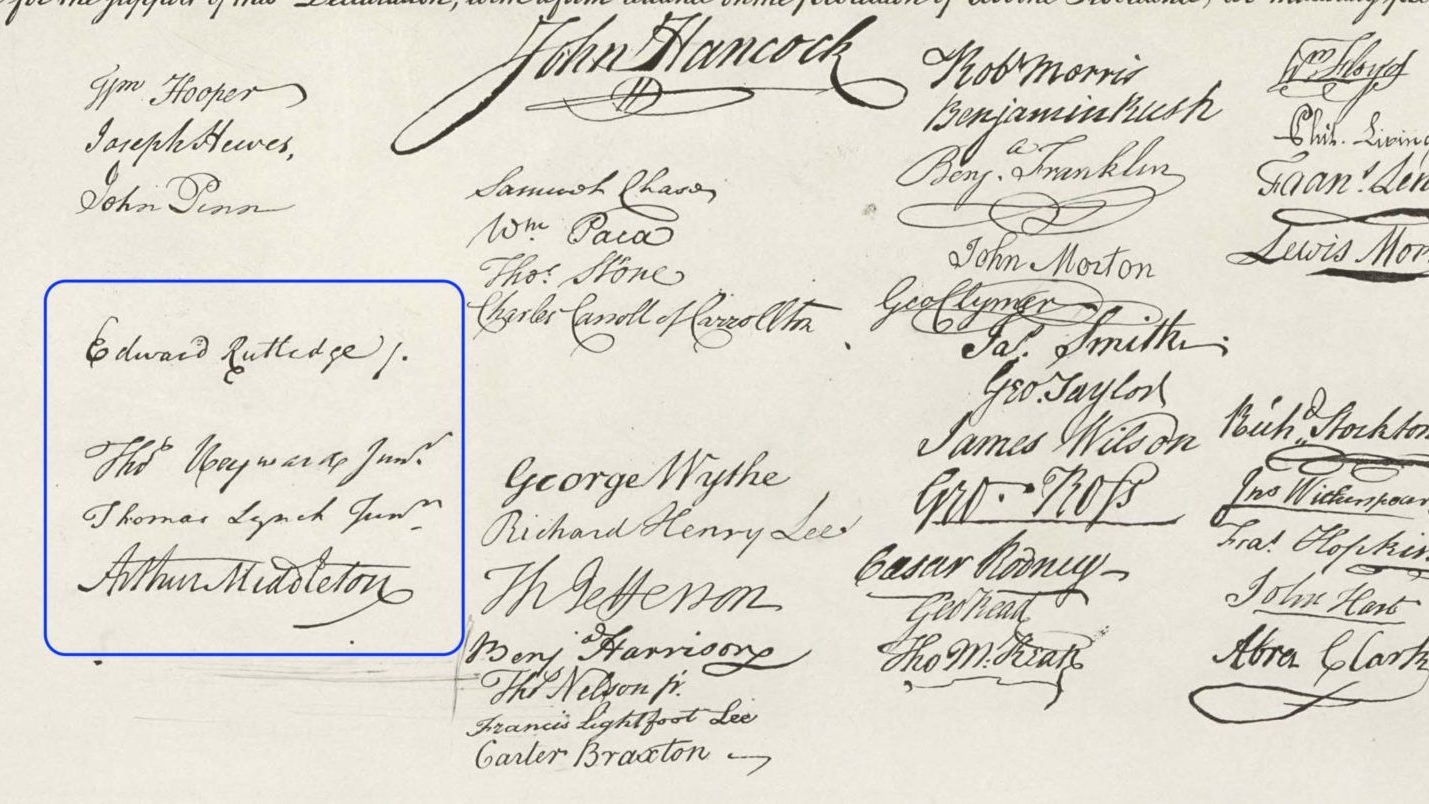

Signatures on the United States Declaration of Independence, Aug 1776. Signatures of the four South Carolina delegates are in the blue box.

Introduction

William Sams fled with his family to the Beaufort area from Charleston in 1783. He left Charleston because of the Confiscation Acts of early 1782. They likely picked Beaufort due to family connections. As our past DHF president, John Colgan, might say, it was the second time the Sams were on the wrong side of history. But similar to the first time, this move was a blessing in disguise. The following 80 years would bring great wealth to Beaufort, South Carolina, and the Sams. This short article is about how we won our independence from Great Britain, seen through the lens of local South Carolina’s concerns and consequences.

What’s most interesting is the Declaration of Independence directly connects to Beaufort and Datha Island!

First Continental Congress – 1774

An early decision of the First Continental Congress adversely affected Beaufort and soured support for the independence movement here. The Continental Congress enforced a strict embargo on all trade with Great Britain. The South Carolina delegation lobbied successfully to free rice from the blockade, but not indigo. Indigo was the pillar of the Beaufort Sea Islands’ economy in the three decades before the American Revolution, not rice. The Royal Navy used indigo cakes primarily imported from the Lowcountry in making their uniforms. This effort of the nascent American Revolutionary government to embargo indigo but not rice did not sit well in Beaufort. The decision was a blow to Beaufort’s economy; worse, none of the SC delegates who voted for the embargo were from the Beaufort District. When the First Provincial Congress met the following year, representatives from Beaufort District were included, and the rice/indigo disparity was partially resolved[Rowland.]

As you might expect, smuggling indigo out of the Lowcountry quickly became problematic when the embargo set in. It was a distraction that bred distrust and impeded local patriotic efforts to resist the British. The smuggling pipeline went down Skull Creek (on the north side of Hilton Head Island) to Savannah, GA, and on to St. Augustine.

Once “the shot heard round the world” was fired at the Old North Bridge in Concord, MA (April 1775), events started to move quickly. The Colonists had to hang together if they were to have a chance at winning. It was time for Beaufort District to take up arms against the British. Some did, but some did not. St. Augustine, FL, was a critical British stronghold for nearly the entire war. Beaufort’s proximity to the Atlantic sea lanes of communication, proximity to St. Augustine, and its location between Charleston and St. Augustine were key reasons so much of Beaufort District was destroyed as the armies and militia clashed.

Patriot Colonel Stephen Bull commanded the militia forces in the Beaufort District. He achieved an early victory in June 1775 when, supported by John Habersham and others, they captured a British ship on its way to Savannah with 16,000 lbs of gunpowder. This vital resource was divided between the patriotic forces in GA and SC; some was stored in Old Sheldon Church, some made its way to General George Washington’s army, then under siege at Boston. Two months later, another patriotic victory resulted in the capture of 11,000 lbs of gunpowder. This victory increased the powder stored in Charleston (for defending the entire colony) by a factor of ten.

The Battle of Sullivan’s Island (near Charleston) in June 1776 was another American victory. For the next three years, relative peace fell over South Carolina.

Second Continental Congress – 1776

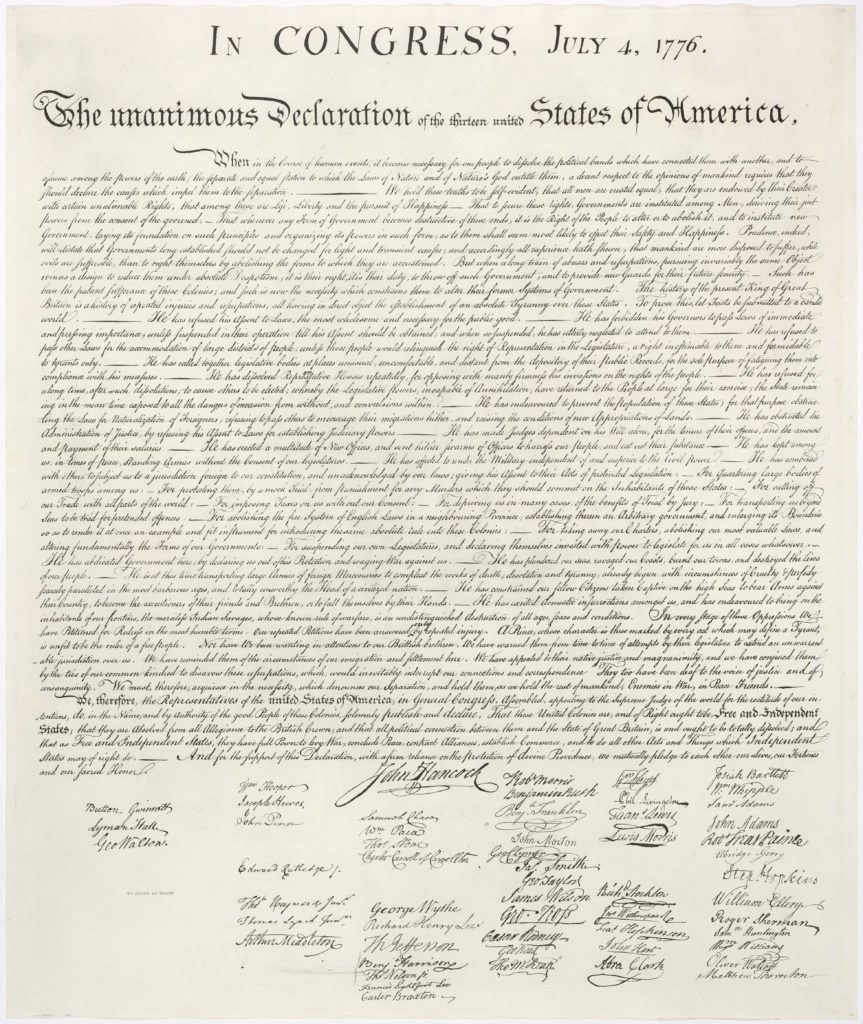

In July of 1776, Thomas Jefferson, in consultation with the Committee of Five (i.e., himself, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston), was racing to draft and present a Declaration of Independence from the British Empire to the Second Continental Congress. It was debated in Congress and agreed to on July 4th. The final document contained twenty-seven grievances.

The fourth grievance, referring to the King and the British government, stated. “He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.”

As Professor Rowland explains in chapter 11 of his first volume of the History of Beaufort County,

“…places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant…” was referring to the Beaufort Assembly of 1772.

For years, the administration of the royal government of South Carolina was centered in Charleston. In 1772, Governor Lord Charles Greville Montagu “…devised the constitutional operation of moving the place of assembly from Charleston to Beaufort.” [Rowland, page 195] The governor had hoped this would hamper the hostile Charleston men from attending or attending for long. He also believed he might curry favor with the Beaufortonians. He not only did not succeed with either objective, but the whole fiasco spilled beyond South Carolina to become, four years later, one of the twenty-seven grievances against the King!

The Continental Congress printed multiple copies of the Declaration of Independence in newspaper form (i.e., broadsides) and distributed them to the thirteen colonies. At that point, this secret document and three names became public. The authorizing name printed on the broadsides was that of the President of Congress, John Hancock. Also identified were Congressional Secretary Charles Thomson and the Philadelphia printer John Dunlap. However, there were no signatures yet.

Congressional Clerk Timothy Matlack handwrote a parchment copy signed by Congress members the first week in August 1776. And here we are, 246 years later.

With this act, the 56 delegates signed their death warrants in the eyes of the British Empire. The war would continue for seven more years.

The four signatories from South Carolina to the Declaration of Independence were:

Thomas Lynch, Jr. (1749 – 1779) – He and his wife were lost at sea while traveling to Europe. He was seeking a better climate for health reasons.

Edward Rutledge (1749 – 1800) – the youngest signatory at 26, was taken as a POW after the British siege of Charleston and later became Governor of SC.

Thomas Heyward, Jr. (1746-1809) – Born in St. Luke’s Parish (Beaufort District), was taken, prisoner. He was the most ardent revolutionary from Beaufort District [Rowland]).

Arthur Middleton (1742 – 1787) – Also taken prisoner, had a United States Navy ship named after him in WW II.

When they signed our Declaration of Independence, they ranged in age from 27 to 34.

End of the Revolutionary War in South Carolina

Over 200 battles were fought in South Carolina during the war, six of which were in the Beaufort District. Here are a few details.

Battle of Port Royal Island (Battle of Beaufort), February 1779

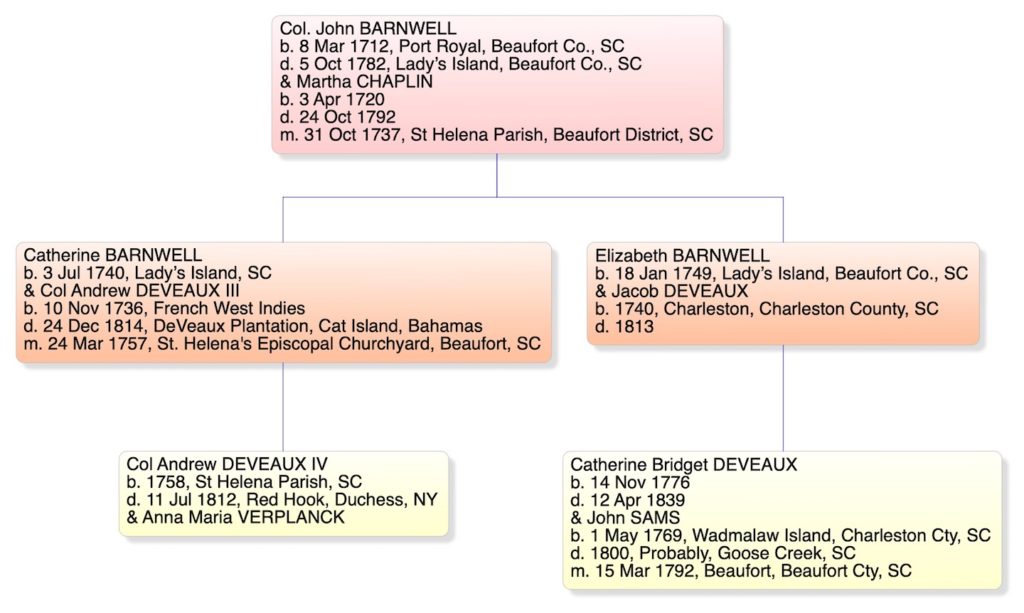

Inconclusive, Americans declared it a victory because they had fewer casualties, and their militia beat British Regulars in open-field combat. The two British soldiers buried in St. Helena’s Episcopal Churchyard, Beaufort, SC, fell at this battle and were buried there under orders from patriot Capt John Barnwell. Native son Andrew DeVeaux IV defected to the British side before this battle and became a staunch Tory throughout the rest of the Revolutionary War. He was born and raised here, and his area knowledge was invaluable to the British cause. I’ll come back to him in a minute.

Battle of Coosawhatchie, May 1779

This British victory resulted in their occupation of the town of Beaufort. Tory Andrew DeVeaux admits to burning Prince William Parish Church (Old Sheldon Church), built on Bull family land at their own expense. He hated the Bulls. After the war, he and many Loyalists fled to the Bahamas.

Battle of Stono Ferry, June 1779

This was an American victory for Charleston, but not Beaufort and not the enslaved that the British had ‘liberated’ along the way. The battle was fought near Charleston, but it was the successful British retreat to Beaufort that historians admire. Their ability to move so large a force across four large tidal rivers and the St Helena Sound back to Beaufort was surprising. The large number of enslaved people liberated by the British became a burden to them. In the retreat, the British abandoned most of the enslaved on Otter Island (in St Helena Sound), where African-Americans perished by the hundreds.

Fall of Charleston, May 1780

“The surrender of Charleston was the worst single defeat suffered by Americans in the Revolutionary War.” [Rowland, pg 231] Captured Beaufort Patriots were put on the prison ship Pack-Horse for a year. POWs were John, Robert & Edward Barnwell, Henry W. DeSaussure, William Elliott Jr., Benjamin Guerard, Thomas Grayson, James Heyward, John Kern, and William Hazzard Wigg. The most critical Patriots POWs were sent to the ancient dungeons of the Castillo San Marcos in St. Augustine. Three of the four SC signers of the Declaration of Independence were taken prisoners in Charleston. The fourth, Thomas Lynch, Jr., had been lost at sea with his wife in 1779.

Confiscation Acts of 1782 & William Sams

As the war was winding down in 1782, the General Assembly met at Jacksonburgh from January through February and passed the Confiscation Acts. The lists of names accompanying the acts were printed in newspapers across the state, identifying levels of punishment. Included in these records was William Sams.

The lists were grouped by offense severity against the patriotic cause of independence. The most extreme penalty is “their Estates Confiscated & their Persons to be Banished from the State.” The least severe punishment was for persons whose “Estates are amerced a fine of 10 percent ad valorem.”

William Sams was on the list with 47 others whose estates had amerced a penalty of 12 percent of their value. (Amercement was directed toward those who had wavered in their allegiance but had repented and taken a loyalty oath.) Five gentlemen appealed, including Williams Sams.

William won his appeal, though what happened to his estate on Wadmalaw Island is unclear. In any case, once his name publicly appeared on a list associated with the Confiscation Acts of 1782, it meant he was a bit tainted, at least in that time and place.

In December 1782, the British garrison evacuated Charleston. The war was over in South Carolina, though skirmishes and reprisals continued between Patriots and Loyalists.

William and Elizabeth Sams

I hope you can better appreciate the situation William Sams faced in 1783. The British had occupied Charleston and its vicinity for the previous two and a half years. While the British were gone, anyone perceived as having offered aid and support to the British occupying force was subject to reprisal. William Sams was one of them.

Rowland has a great epilogue to the war, where he addresses the fate of prominent Beaufort Tories. Some went to Florida, some to England, and others to the Bahamas.

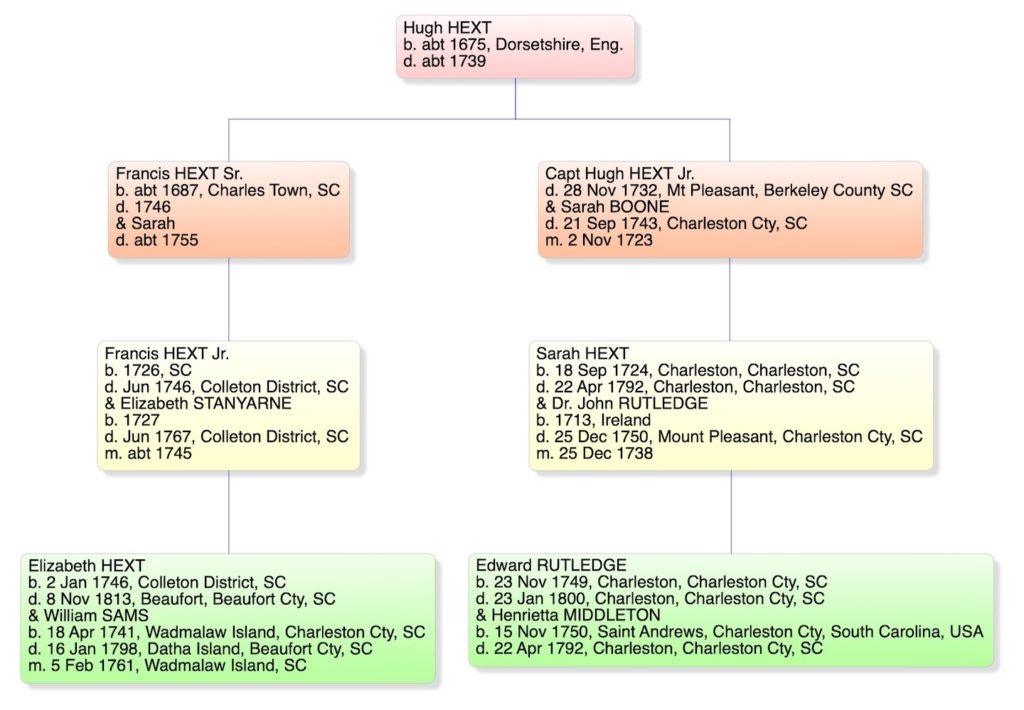

As you can see, William Sams and his family left Charleston but stayed in South Carolina. Even though he successfully argued his case about being neutral throughout the war, he probably felt that was not the end of reprisal efforts. But why go to Beaufort District and Datha Island? Because of family connections.

William’s uncle Nathaniel Barnwell (1705-1775) was “..the most productive indigo planter in the Beaufort District.” [Rowland, pg 165] Also, William’s wife Elizabeth Hext Sams (1746 – 1813) had ancestors that bought land in the town of Beaufort before 1759 [SCDAH], and her granduncles inherited six hundred acres of land on St Helena Island in 1741. William Sams must have heard about and visited the area before 1783. He expected that he could prosper again in this corner of South Carolina. William Sams purchased Datha Island from his cousin Sarah Reeve Gibbes (1746-1825) in May 1783 but had moved to the area a few months earlier [Bond].

I wonder if he had any idea what good fortune lay ahead?

Cotton becomes King

By the early 1770s, planters across South Carolina scrambled to find other profitable crops. Rice had been a flywheel for the South Carolina economy since 1685. It brought the plantation system to the colonies. Indigo was heartily welcomed when it came along in 1744 since it had a ready market: the British Navy. In Beaufort, there was another huge advantage to indigo; it could be grown inland, where rice flourished, and on the sea islands. At the outset of the American Revolution, a significant part of the market for indigo from South Carolina was gone. The pressure was building for another profitable crop.

The void left by the collapse of the indigo market was soon filled by long-staple cotton, which arrived on Hilton Head Island in 1790. A land rush on the South Carolina sea islands followed, the only place this exceptional cotton could thrive. (Some sea island cotton was grown in Georgia and Florida, however, the vast majority was from South Carolina.)

Any land suitable for cotton cultivation was in high demand, whether inland or on the sea islands. Between 1793 and 1801, South Carolina’s cotton production rose from 94,000 to 20 million pounds, and by 1811, cotton production had passed 40 million pounds [South Carolina Encyclopedia.]

The wealth generated by the subset of long-staple cotton, known as sea island cotton, was unbelievable: 500M lbs of sea island cotton was exported from Charleston over 55 years (1805-1860). This exceptional cotton sold for an average of about 31 cents per pound over that period [Porcher.]

When 1860 dollars are converted to 2022 dollars, that 500M lbs of Sea Island cotton was valued at $ 5.4 billion (2022$)! Not Millions, but Billions!! This is the fortunate situation William and Elizabeth Sams were about to encounter when they bought Datha Island in the spring of 1783.

However, the land rush and the wealth generated by cotton also led to a boom in slavery. Cotton’s arrival after the American Revolution changed our nation’s destiny in many ways.

Cotton generated incredible wealth for a few but required great suffering by many.

Bill Riski

June 2020

Epilogue

Two of the gentlemen mentioned above are Edward Rutledge and Andrew DeVeaux IV. Edward was an American Patriot, and Andrew was a British Loyalist. Both were related to ‘our’ Sams!

Patriot Edward Rutledge, the youngest signer of the Declaration of Independence, is a 2nd cousin of Elizabeth Hext Sams.

Loyalist Col Andrew DeVeaux IV, who admitted to burning down the Old Sheldon Church in 1779, is a 1st cousin of Catherine DeVeaux Sams, wife of John Sams, William & Elizabeth Sams’s oldest son.

Sources

Barnwell, Stephen B – The Story of An American Family, 1969.

Bond, Lula Sams and Sanders, Laura Sams – The Sams Family of South Carolina, South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 64, No. 1 (Jan 1963), pp. 39-52

Holden, Joel and Riski, Bill – The Sams Family Tree, Ancestry.com, accessed 1 Aug 2020.

Porcher, Richard D. – The Story of Sea Island Cotton, 2005

Rowland, Lawrence S., Moore, Alexander, Rogers Jr., George C. – The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina, Volume I, 1514 – 1861, 1996, chapters 10 – 14.

South Carolina Department of Archives and History (SCDAH), Land Record for Town Lot No. 91 in Beaufort, October 1759.

South Carolina Encyclopedia-Agriculture. Accessed June 2022.

South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 34, Oct 1933, pp. 194-199

Wikipedia, Topic = United States Declaration of Independence, South Carolina & Signatories of the United States Declaration of Independence. Accessed 9 July 2022.

#52Sams