The photo above is of Drimnagh Castle in Dublin, Ireland. It’s the ancestral home of the Barnwell (de Bernival, Barnewell, Barnewall) family. The castle you see dates to the 15th century. It has been partially restored and is open to the public today.

Never trust a Spaniard, nor be afraid of an Indian.

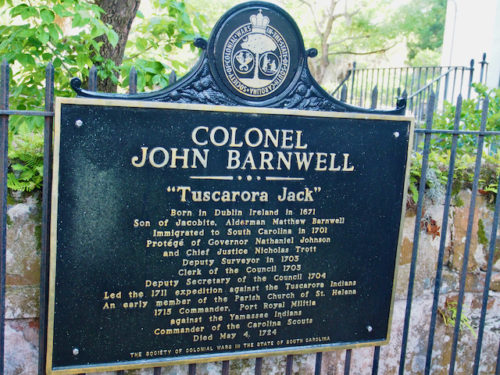

Col John Barnwell

(Rowland, Volume 1, page 104)

Fresh Start

In a previous article, I told you about William Sams’ paternal grandfather, Bonum Sams II, whose ‘fresh start’ was as an indentured servant in the late 1600s. Here, I present his maternal grandfather, John Barnwell.

John Barnwell was born in Dublin, Ireland, the son of Alderman Matthew Barnwell and Margaret Carberry. Matthew Barnwell was killed in the Siege of Derry in 1690 as a captain in King James II’s Irish Army, which failed in their attempt to restore the last Stuart king to the English throne. The family seat, Archerstown in County Meath, was forfeited due to these events. John eventually took flight for North America in 1701. He became a colonist in the territory, then called Charles Towne in the colony of Carolina. His timing coincided with the emergence of the rice culture and the associated prosperity. [Rowland, Volume 1]

He rose under Governor Sir Nathaniel Johnson to the Deputy Secretary of the Governor’s Council within ten years. He married Elizabeth Anne Berners in 1702, and they had two sons and six daughters over the next eleven years. As a surveyor, he mapped the newly settled Sea Islands around Port Royal Sound. It was there that he staked his claim to 6,500 acres of land. Barnwell became one of the first Anglo-Celtic settlers of Port Royal Island and an active trader with the nearby Yamassee Indians. John was relied on to manage trade relations with the Native Americans and served as a militia officer in skirmishes against the Spanish and French further south. [Rowland, Volume 1]

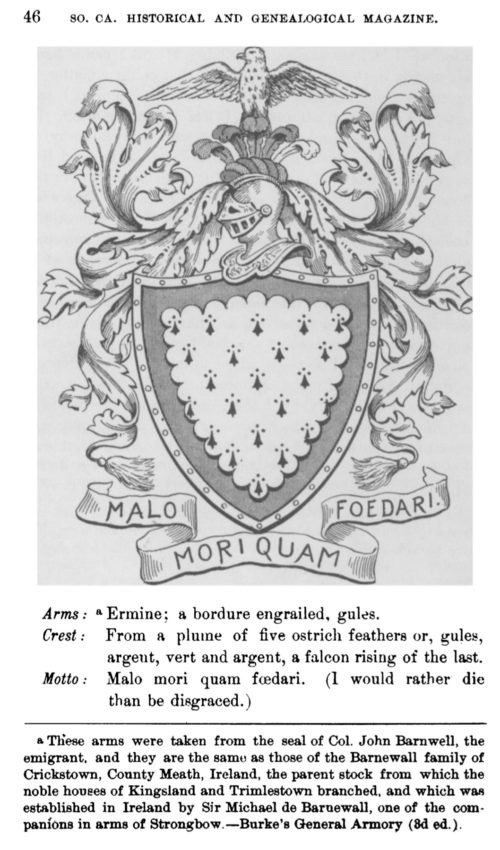

I would rather die than be disgraced.

From Coat of Arms of Col John Barnwell

Indian Wars

Encroachment by the European settlers on Native American lands created tensions that erupted in September 1711. The Tuscarora tribe, with 1,000 warriors, attacked and killed or captured as enslaved people over 200 settlers. This Tuscarora War set up a chain of events that lasted six years. In the province of South Carolina, Governor Gibbe’s commissioned John Barnwell as a Colonel, supplied him with men and provisions, and sent him off to conqueror the Tuscarora Indians. To do this, Col Barnwell enlisted the help of other Indian tribes, particularly the Yemassee. His ‘army’ left Charles Towne in the winter of 1711 and marched 200 miles north through swamp and forest in the rain, snow, and ice. By July 1712, he returned triumphantly to Charles Towne, where a thankful assembly nicknamed him “Tuscarora Jack.” Within a few years and after more conflict, most of the remaining Tuscarora tribe left the Carolinas and migrated to northern New York. They became the sixth nation of the Long House of the Iroquois. However, peace did not last.

The same Yemassee Indians who had helped defeat the Tuscarora Tribe turned on the settlers in April 1715. In their attack on Pocotaligo Town (today’s Yemassee, SC), only 2 or 3 settlers survived. One swam the river over to John Barnwell’s plantation (called Doctors Plantation on the north side of Port Royal Island). John and Elizabeth’s oldest son, Nathaniel, was only ten. He and others escaped by ship, but nearly all the British colonists south of Edisto Island were killed. The Yamassee’s initial victories sent alarms for the very survival of English colonists far up the coastline to New England. Governor Craven declared martial law in the province and assigned Lt Col Alexander Mackay and Col John Barnwell to retake Port Royal and Pocotaligo. At the same time, the Governor and his militia marched south from Charleston to join Mackay and Barnwell. They drove the Native Americans to St. Augustine. When the hostilities finally subsided two years later, over 400 colonists had perished.

Consequently, the settlers rebelled against the proprietary government, angry that the Lord Proprietors’ interests did not adequately include protection during the war. By 1719, the colony’s wealthiest and most influential men demanded an end to proprietary rule and establishing direct royal government from England, “taking the government of South Carolina into the King’s hands.” Proven in battle, Col John Barnwell was chosen to present the case against the proprietary system of governance to the British government in London and request resources and support for building a line of defensive forts at South Carolina’s southern border.

As a veteran of Queen Anne’s War, of the Tuscarora War, and of the Indian rising of 1715, John Barnwell had first-hand knowledge of the Indian and Spanish frontiers from Virginia to the neck of Florida,moreover as the greatest planter of the Port Royal district, he had a direct interest in safeguarding the harrassed southern border. His career in provincial office gave him standing as a colonial expert which the average agent, chosen from the merchant group in London, seldom possessed.

Dr. Verner W. Crane (1889 – 1974)

Professor of History at the University of Michigan

John Barnwell arrived in London in the late spring of 1720 and returned to a hero’s welcome in Charleston harbor aboard the H.M.S. Enterprise on 22 May 1721.

John Barnwell’s plan for a line of defensive forts along South Carolina’s southern border did not materialize as he had hoped. He had presented this plan to the British Board of Trade in 1720, emphasizing the French threat and the need to secure the Altamaha River region. While the Board of Trade initially approved his plan, the British government had limited funds available. Only one fort was approved and built (1721) – Fort King George on the Altamaha River. This fort became the first permanent English presence in what would later become Georgia. In 1724 Col John Barnwell passed away; no one stepped up to carry his plans forward. Six years after its construction, Fort King George was abandoned.

Maternal Grandfather of William Sams (1741-1798)

Col Barnwell continued his responsibilities of defending the colony’s southern border and serving on an Indian Commission until his death in 1724 at age 53. In his will, he bequeaths 4,500 acres, and two lots in Beaufort, to various children. Col John “Tuscarora Jack” Barnwell is buried in Saint Helena’s Churchyard in Beaufort. Unfortunately, we do not know where Elizabeth Anne Berners Barnwell is buried. To connect the dots, John & Elizabeth Barnwell’s daughter Bridgett Barnwell (about 1709 – 1741) married Robert Sams (about 1706 – 1760) and had a son, ‘our’ William Sams. Bridgett brought into the marriage 500 acres at Scull Point on Hilton Head that her father left her in his will. [The origin of the name Scull is unknown. Through phonetic simplification it evolved into Skull, as in Skull Creek.]

Sources

Barnwell, Stephen B., The Story of An American Family, 1969.

Riski’s commentary: This book is exceedingly hard to find. However, the Beaufort District Collection in Beaufort Public Library on Scott Street in Beaufort, SC has a copy available for the public to read, but not checkout. This book is an amazing compilation of facts, family stories, and photographs of nearly four hundred years of the Barnwell family of South Carolina from John Barnwell on down. Chapter 1 is a wonderful, extensive biography of John Barnwell.

Rowland, Lawrence S., Moore, Alexander, Rogers Jr., George C. – The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina, Volume I, 1514 – 1861, 1996.

Riski’s commentary: Chapter 5 Yemassee War provides a sobering view of the dangerous times the Carolina colonists lived in from 1715 – 1728.

Rowland, Lawrence S., South Carolina Encyclopedia, John Barnwell, 2016.

Source: The South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Jan. 1901), pp. 46-88

Published by: South Carolina Historical Society

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27574942

Wikipedia entry for King James II

Riski’s commentary: This Wikipedia entry is interesting reading. It gives you a sense of the political and religious elements in play at the time.

52Sams, Week_02, John_Barnwell (1671 – 1724)