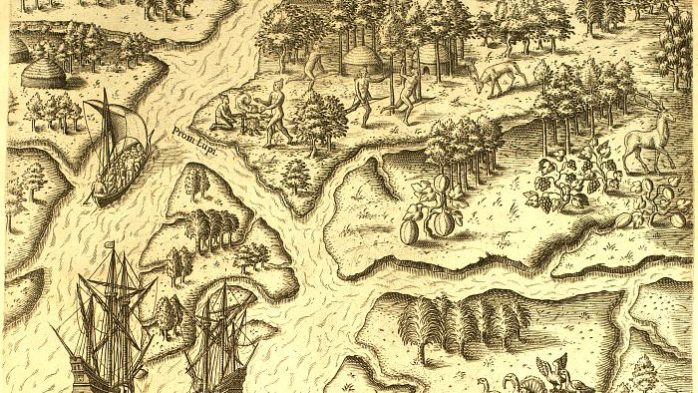

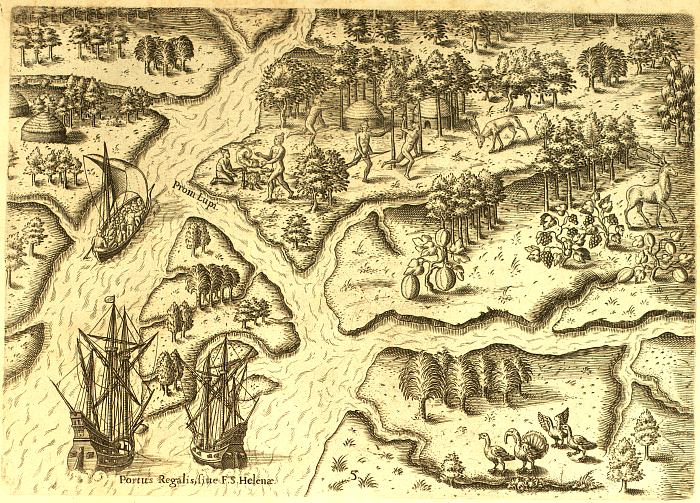

Depiction of Native American life in Port Royal Sound by Jacques le Moyne de Morgues (1533–1588)

Like all of the United States, the Lowcountry was inhabited by indigenous peoples when Bonum Sams II (1663 ~ 1743) and John Barnwell (1671 – 1724) immigrated here in 1681 and 1701, respectively. Nineteen American Indian tribes lived in our area at one time. However, their numbers were diminished by inter-tribal conflicts (usually against non-Coast Indian tribes), warfare with the Spanish, French, British, Scots, and disease. Before William Sams (1747 – 1798) bought Datha Island in 1783, the American Indians were gone from this corner of South Carolina.

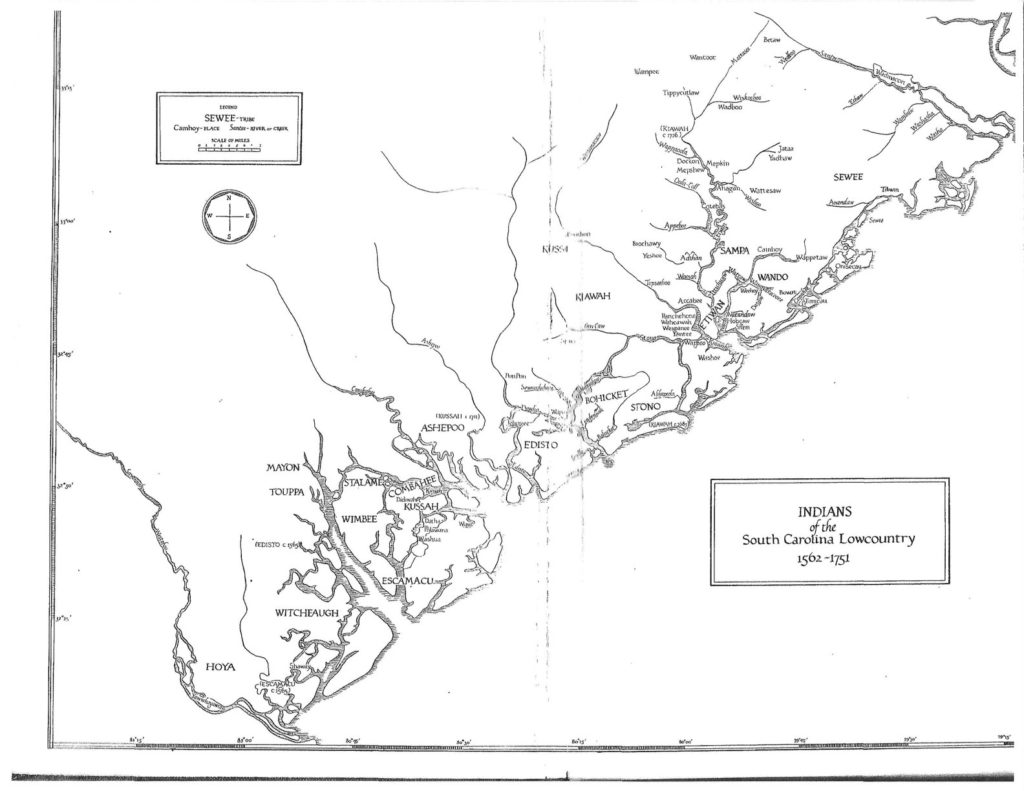

While researching my article Dataw Island on Datha Island, I discovered Gene Waddell. He was the expert Arthur Levin from ALCOA talked to 40 years ago about our island’s name. The map below comes from his scholarly book, Indians of the South Carolina Lowcountry 1562 – 1751 (available from the Beaufort County Library system.)

Nineteen American Indian tribes

Nineteen American Indian tribes lived along the coastline, or within 80 miles of it, from the Santee River on the north (just below Georgetown, SC) to the Westobou River (for the Westo tribe) on the south. Haven’t you heard of the Westobou River? I’m not surprised. Today it’s called the Savannah River. Gene Waddell calls this area between the Santee and the Savannah the Lower Coast. I continue to be amazed at the places around us that have an American Indian name as their root. Some have stuck, and some have not. Most are phonetic spellings of a word whose accurate pronunciation was lost over the years. One example from close to home is Coosaw Island, just north of us. The island is named after the Kussah tribe.

At the other extreme is Combahee Island, named after the Combahee tribe. Or at least it was until a pesky governor put his mark on it. In 1698 the island was renamed by Joseph Blake, governor of colonial South Carolina, in honor of Lady Elizabeth Axtell Blake, his wife. Today Combahee Island is Ladys Island. No American Indian root is left in that name, though the river was left untouched.

Note that the largest print on the map is for the nineteen tribes who lived in this area from 1562 to 1751. Starting from the top of the chart (i.e., northeast), the tribes were Sewee, Sampa, Wando, Etiwan, Kussoe, Kiawah, Bohicket, Stono, Edisto, Ashepoo, Stalame, Combahee, Kussah, Wimbee, Escamacu, Mayon, Touppa, Witcheaugh, and Hoya.

Not all tribes survived that long. Their numbers were diminished by inter-tribal conflicts (usually against non-Coast Indian tribes), warfare with the Spanish, French, British, Scots, and disease. The locations of the tribes on the map are their summer villages. In the wintertime, they moved inland and upstream and formed smaller communities. However, they seldom went more than 80 miles inland for fear of encroaching on lands inhabited by tribes in the Appalachian Mountains, like the Cherokee.

Timeline of the Lower Coast Indians

Based on Waddell’s extensive discussion, this is my synopsis of 200 hundred years of European contact with these tribes.

1562

The French and Spanish occupation begin in the southern end of the Lowcountry. The Escamacu War (1576 – 1579) and other European conflicts caused all indigenous tribes to move further north toward Charleston. By 1580, the Indians deserted the area between the Savannah River and the Broad River. For the next 100 years, the Indians came and went seasonally, as they’d always done, from the Atlantic in summer to the inland forests in winter.

1675

Skirmishes with the English in Charleston picked up, and the individual tribes began to demand land be ‘reserved’ for their use. While this was done, there was no enforcement by the British to keep Europeans, including British settlers, out of the reserved land. By 1683, Scottish emigrants were settling in the Port Royal area. Also, the Yemassee tribe moved there. This made the area a hot spot. Conflicts arose with the Spanish to the south and with coastal tribes who had gradually returned to their ancestral Port Royal area. The Lord Proprietors reacted by declaring all lands from the Appalachians to the Atlantic belonged to the Proprietors. Tensions eased as Coastal Indians moved further north to St Helena Sound. Unlike one hundred years earlier, the English settlers filled the void by acquiring the deserted land. In light of this development, Indian reservations were established.

1712

The first Indian reservation in South Carolina was established on Polawana Island for the Cusabo tribe. Historians have disagreements about whether ‘Cusabo’ referred to a distinct tribe or all tribes that lived along the Coosaw River. By 1738 the Polawana Reservation is empty. The Indians living there had either died or left the area. The island is re-reserved for a new immigrant tribe called the Notchee or Natchez. They were not part of the nineteen indigenous coastal Indian tribes. The English brought in Natchez Indians to serve as lookouts/scouts against Spanish invaders encroaching on Port Royal.

1751

The last indigenous coastal tribe mentioned in the Commons House of Assembly of SC’s historical records is the Etiwan. The Coastal Indians, all nineteen tribes, were on the brink of extinction.

1783

When William and Elizabeth Sams move to Datha Island, all indigenous peoples’ remnants are gone, except for the middens (i.e., shell mounds).

The lifestyle of the Lower Coast Indians

On the Lower Coast, the tribes subsisted on agriculture (e.g., corn, peas, and beans), hunting in fall and winter (e.g., deer and turkey), gathering (e.g., roots, acorns nuts, hickory nuts, berries, shellfish), and fishing (e.g., sturgeon, bass, drum, mullet, trout).

Clothing was optional. The only surviving drawing of Lower Coastal Indians shows them without clothes. This was typical for tribes elsewhere in the Southeast also. Since the main problem this presented was biting insects, they oiled themselves with bear oil. This was also used to clean their hair. It’s reported that the oil had no smell. Of course, this did not please the Spanish missionaries. When the Indians did wear clothes in the colder seasons, it was made of deer and bearskins. They painted their faces and wore feathers and beads to intimidate and celebrate.

One notable difference in their culture, as recorded by the Europeans, was the status of women. Waddell says,

“At least two tribes had women chiefs, and a third tribe had as many women leaders as men. A fourth tribe had women presiding to receive visitors.” This was not common in other places in the Southeast.

The coastal tribes were also unique in that they were monogamous.

One enduring mystery is their language. No texts have survived for any of these tribes. As best we can tell, at least two languages were used on the Lower Coast. One language is known to have been Siouan, but the other is still unknown. Siouan was spoken north of the Ashley River, and a different language(s) was used south of the Ashley. Whether the second was several languages or one with distinctly different dialects is still unknown. Records from the 1560s reveal that missionaries had to be assigned to specific geographic areas to ensure they could eventually learn the local language. They then had to start over when set to a different location. We know Yemassee Indians spoke either Creek or Muskhogean language, but they were not indigenous to the Lower Coast like the other nineteen tribes.

The Drawing

Some of what we know is supported by drawings that depict the Coastal Indians. But caution is needed here. Many illustrations are attributed to either Jacques Le Moyne or Theodor de Bry.

Jacques le Moyne de Morgues (c. 1533–1588) was a French artist and member of Jean Ribault’s expedition to the New World. His depictions of Native American life and culture, colonial life, and plants are extraordinary historical importance. The good news is he did travel to the New World and is an eyewitness to see native Indians in the Southeastern area, including Port Royal Sound, in 1564. He was a talented artist who drew what he saw while here. The bad news is the Spanish captured him, sent le Moyne back to Europe, and only one of his drawings survived! A few years later, he redrew them from memory, and therein lies the rub.

Theodor de Bry (1528 – 1598) was an engraver and publisher famous for depicting early European expeditions to the Americas. De Bry created a large number of engraved illustrations for his books. He engraved le Moyne’s recreated drawings and published them. But de Bry himself never visited the Americas and was not consistent in attributing his work to the explorers whose results he published. Scholars have endless arguments about how accurate his published works were.

This is where Waddell’s research is so helpful. While he refers to some of le Moyne’s re-created drawings, he is careful to correlate what he concludes from them with other written records of the time. With this in mind, here is the one illustration of our area that Jacques le Moyne de Morgues re-created circa 1566. It shows a daily scene of Coastal Indians living in Port Royal Sound. I believe the ships are just offshore from Paris Island in this scene.

The Decline

In researching this article, I was surprised by the population of American Indians in the Lowcountry. Waddell relies on a census taken in 1682 of the number of archers in six coastal tribes. Based on how many family members were supported per archer, he estimated 1,000 Coastal Indians existed in 1682. Mr. Waddell then works backward and postulates about 1,750 Coastal Indians (men, women, and children) in 1562. By 1751, no more than 250 Indians are left from the original indigenous coastal tribes. In 200 years, the American Indian population in our area fell by 85%. For every seven Indians alive in 1562, there was only one in 1751. Waddell’s concluding statement is elegantly depressing.

In two centuries of contact with Europeans, nearly six of every seven Indians on the Lower Coast died of causes directly related to them.

Gene Waddell

Epilogue

If you want to learn more about the Lower Coast American Indians, I recommend Gene Waddell’s book, available from the Beaufort County Library.

His book is in two parts. Part One: Overview is about 80 pages. He describes the 19 tribes, including their locations over time, population, inter-tribal relationships, and much more.

Part Two: Annotated Sources is 275 pages. He is meticulous in describing the sources he used. Sources are organized by tribe and Indian place names! Datha, for instance, gets three pages. This part also includes 100 pages of footnotes and a bibliography.

Sources

Rowland, Lawrence S., Moore, Alexander, Rogers Jr., George C. – The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina, Volume I, 1514 – 1861, 1996

Waddell, Gene – Indians of the South Carolina Lowcountry 1562 – 1751, published 1980.

#52Sams – Lower Coast American Indians