Köhler, Franz Eugen, Botanical illustration of Gossypium barbadense plant (extra-long staple cotton, Sea Island cotton), 1897

By 1850, his two sons had amassed a fortune well in excess of four hundred thousand dollars.

Rowland, et al., Volume 1, page 372

The authors referred to Lewis Reeve Sams (1784 – 1856) and Berners Barnwell Sams (1787 – 1855), the sons of William Sams and Elizabeth (Hext) Sams, who owned plantations on Datha Island and elsewhere in Beaufort County for about 50 years in the 1800s.

$400,000 in 1850 is worth $14,417,846.15 today

CPI Inflation Calculator

Of course, everything has gone up in cost over this timeframe, but still, they were wealthy. Such was the prosperity derived from the cultivation and sale of Sea Island cotton in the Lowcountry of South Carolina in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Because William Sams felt he was no longer welcomed in the Charleston area after the American Revolution, he and Elizabeth moved their family to Beaufort in 1783. Unfortunately, he did not live long enough to appreciate what a blessing that would be. The story of Sea Island Cotton is about being in the right place at the right time.

However, the awful side of this story is that Sea Island Cotton, like all cotton, was only this profitable in the antebellum era when enabled by slavery. Though it generated enormous wealth for a few, it required great suffering by many.

Demand for Cotton

Cotton has been cultivated in North America since the earliest days of European exploration in the 17th century. But several factors converged in the 18th and 19th centuries to form the catalyst for cotton’s explosion onto the fields of the South.

King Charles II implemented policies in the mid-1600s to encourage wealthy English planters to settle in North America. Plantations with forced labor flourished, cultivating tobacco in the colonies of Virginia and Maryland and rice in the Carolina Colony. However, a lesson learned in the British West Indies was that dependency on one crop was not financially healthy. Weather and market fluctuations could and did destroy many plantation owners’ futures.

In the last half of the 18th century, rice and indigo were the two money crops in the Beaufort District. But indigo was exported to England for dyeing their Royal Navy uniforms. Once “the shot heard round the world” was fired in Concord, Massachusetts, in April of 1775, the British were not keen on buying indigo from their upstart colonies anymore. So when the war ended in 1783, William Sams looked south from the Charleston area to a more friendly political environment and purchased Datha Island from his cousin Sarah Reeve Gibbes. William’s father, uncle, and cousin were all indigo plantation owners, and it’s likely he started (or continued) with indigo on Datha Island. In any case, his timing was fortunate, primarily due to events occurring on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

The French aristocratic taste for fashion was peaking, just as the Industrial Revolution forever changed the textile industry in Lancashire, England. The British demand for raw cotton to weave into fine cloth for France encouraged innovations in powering spindles and looms for making the cloth. Soon the French Revolution freed their citizenry to seek clothing made out of comfortable fabric rather than traditional hemp. This demand further pushed the acceleration of the Industrial Revolution in Britain and the mechanization of looms to produce fine cloth cheaply. By 1860, 440,000 people were employed in 2,650 cotton mills with 350,000 power looms, focused in the region around Lancashire, England.

Throughout this time, the source of cotton to those British looms was the nascent United States. By 1860, 88% of British cotton imports came from America; that is 1,230,607,000 pounds of cotton. Yes, 1.2 billion pounds!

The southern United States cotton belt from the Carolinas over to Texas produced two-thirds of the world’s cotton in 1860. And a portion of this was a particularly fine grade of cotton called Sea Island cotton.

“By all accounts, it was the finest quality of cotton ever grown – anywhere or at anytime.”

Porcher

Sea Island Cotton

These figures above represent all cotton, not just Sea Island cotton. But the Sea Island cotton was unique. Back to William Sams and his sons and good fortune.

The only kind of cotton that would grow on the sea islands of our Lowcountry in South Carolina was also the most in-demand worldwide. None of this was known to William Sams when he bought Datha in 1783. He was stepping into a declining indigo operation. By 1795 Sea Island cotton had arrived in Hilton Head. By 1810, nearly all the land suitable for growing Sea Island cotton was purchased and planted with this unique cotton.

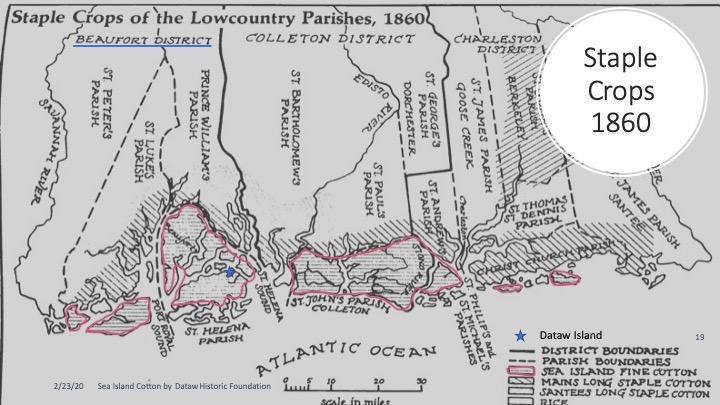

On the map below, I’ve drawn those areas where Sea Island cotton was grown in red.

Cotton & the Sams

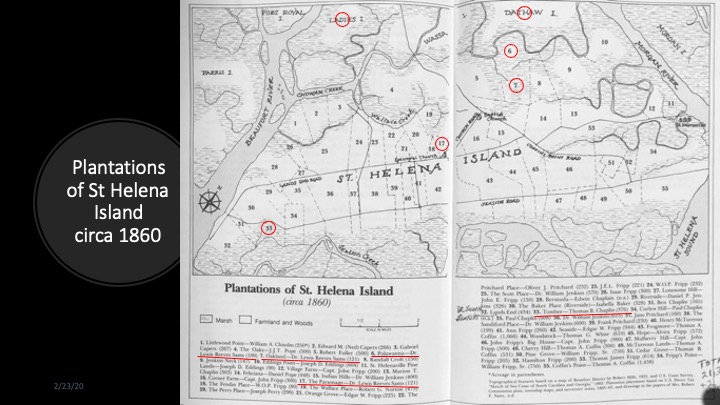

In 1805 and 1808, respectively, the Sams brothers of Datha Island, Lewis Reeve and Berners Barnwell, came of age (i.e., 21) and inherited their plantations from their mother. For the next 55 years, they, and their heirs, reaped the benefits. In 1840, Lewis Reeve Sams had 1,467 acres and 154 enslaved people on Datha. Dr. Berners Barnwell Sams had plantations covering 2,097 acres on Datha & Ladys Island – and 140 enslaved people. And there were other plantation owners in the family then, most notably Dr. L.R. Sams, Jr. (L.R.’s son) – the man who took his family to Texas after the war. He owned three plantations in the immediate area, Polowana, Oakland, and The Parsonage.

The map below shows the locations of Sea Island cotton plantations on St. Helena Island and the immediate vicinity. The upper five red circles denote areas of Sams’ family plantations.

Sea Island cotton was produced by about 350 plantations spread from Hilton Head up the South Carolina coast to Bull Island. Much of the cultivation was done on St. Helena and Edisto Islands. Consider this fact to more fully appreciate Sea Island cotton’s impact on South Carolina in the antebellum era.

From 1805 to 1860, about 500 million pounds of Sea Island cotton were exported from Charleston, most to England and some to New England. This Sea Island cotton would be worth $4 billion in 2022 dollars. Prosperity, but at a price. All cotton was cultivated and prepared for market by enslaved people.

The Cotton Triangle

You can tell how enormous the cotton business was in the 19th Century. The key relationships that enabled all this formed a cotton triangle. [Dattel, page 86]. South Carolina’s cotton was shipped via New York City from Charleston, South Carolina, to Liverpool, England. One surprise to me was the critical role NYC played in this business. New York City handled more imports and exports than all other American ports combined. That made the port of New York enormously important to Washington. The Customs House in New York was the single largest source of income for the government of the United States in the antebellum period.

We often think of the antebellum period as an era of clear slavery versus non-slavery divides, for example, by State. Here’s a fact that illustrates the fallacy in that generalization: Cotton commerce fueled ties between the North and South despite slavery.

In the 1860 presidential election, Abraham Lincoln won the State of New York, despite New York City voting against him, because of the strength of the cotton triangle.

More about Sea Island Coton

My presentation in the Fall of 2019 provided many more details about Sea Island cotton. You can find a link to it in the sources below. In that presentation, I drill down into the cultivation of Sea Island cotton and provide answers to questions like these.

- Why did we have plantations?

- Why did growing cotton require so much labor?

- Why did people in the South believe ‘Cotton is King’?

- Why did the best cotton in the world grow on the Sea Islands of SC?

- Why was Sea Island cotton so valuable?

- Why did Sea Island Cotton disappear?

[Cotton was] a ‘map-maker, trouble-maker, and history-maker.’

David Cohn, in book by Dattel

Education

From a plantation owner’s perspective, the enduring benefit of the antebellum lifestyle was the ability to afford advanced education for men. Professor Rowland reports, “Before the Civil War, no fewer than twenty-five men from the small town attended Harvard.” He was referring to Beaufort. Many others were educated at colleges like Yale, Princeton, Columbia, and West Point.

The Sams were among this educated group. Even after they lost everything in the Civil War, this education enabled many to continue and prosper another day.

Sources

Cook, Grace – Desperately Seeking Softness, Wall Street Journal, Style & Fashion, October 3-4, 2020, page D3

Dattel, Gene – Cotton and Race in the Making of America: The Human Costs of Economic Power, 2009

Köhler, Franz Eugen, Botanical illustration of Gossypium barbadense plant (extra-long staple cotton, Sea Island cotton), 1897

Porcher, Richard D. – The Story of Sea Island Cotton, 2005

Riski, William A. – Superior Cotton from the Sea Islands, 2019 (DHF presentation)

Rosengarten, Theodore –Tombee: Portrait of a Cotton Planter, 1986

Rowland, Lawrence S., Moore, Alexander, Rogers Jr., George C. – The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina, Volume I, 1514 – 1861, 1996

Smith, C. Wayne; Cothren, J. Tom, Cotton: Origin, History, Technology, and Production, 1999

#52Sams – Week 8 – Prosperity