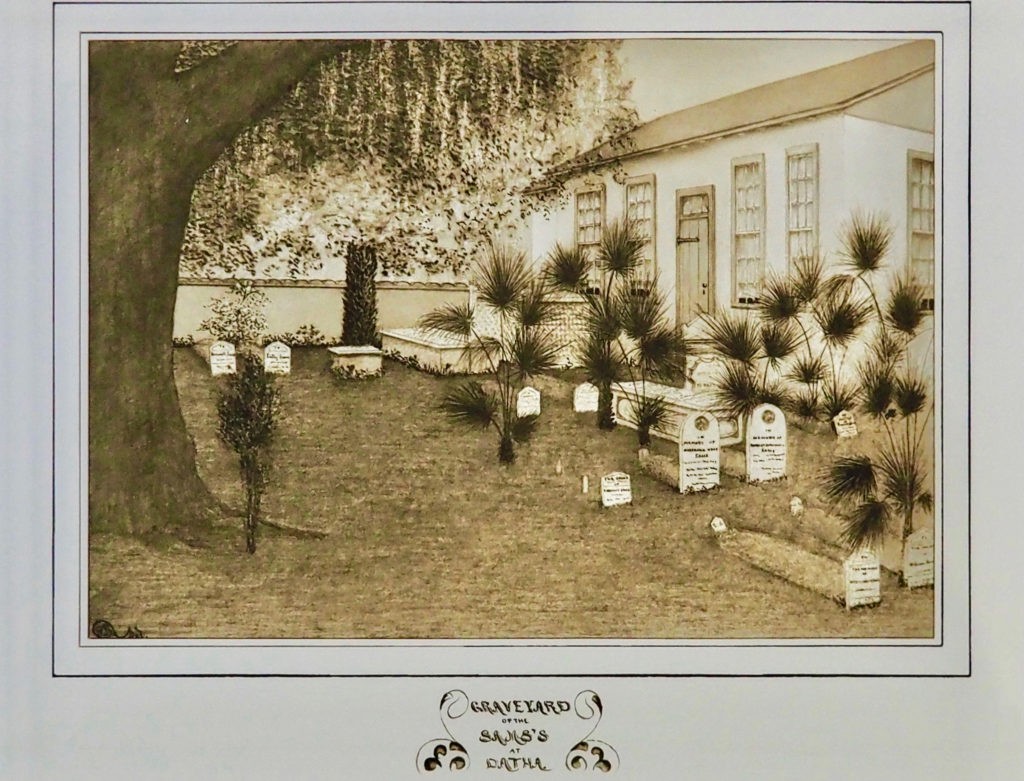

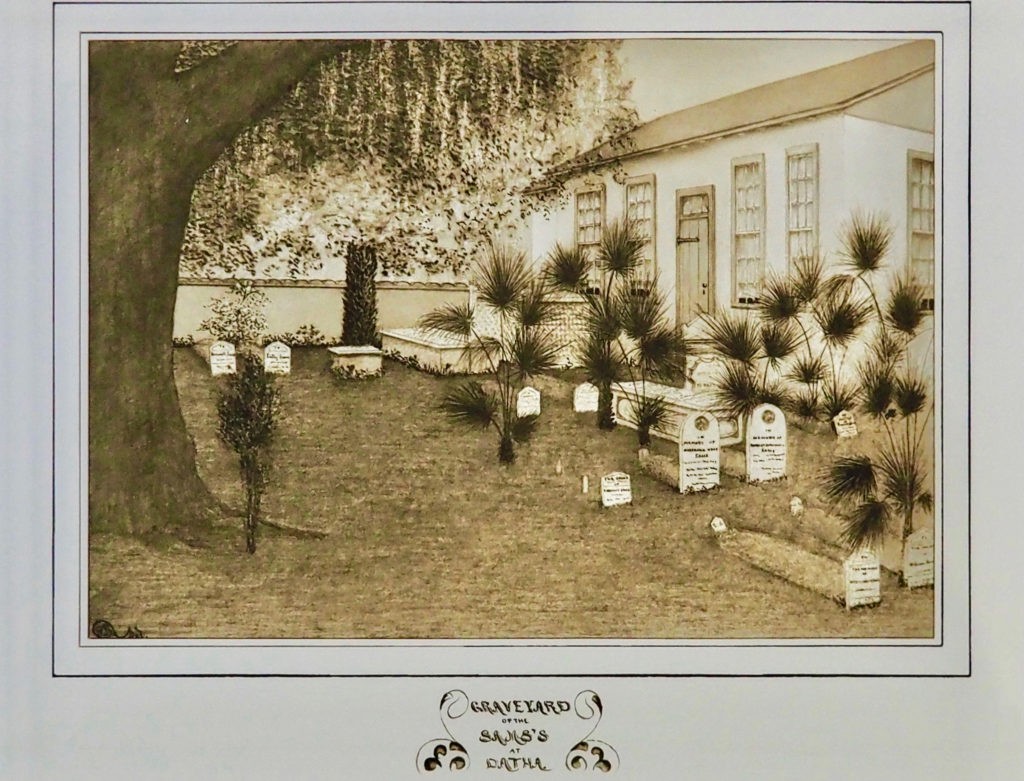

Sams Family Cemetery, Datha Island, SC. Looking southeast towards plantation house.

Photo by Bill Riski, May 2020.

I told you recently about the tripartite plantation house of BB Sams and his wife, Elizabeth (Fripp) Sams. These ruins are always the highlight of the Dataw Historic Foundation docents’ tours. The other site of interest is the Sams Family Cemetery, a short distance from the ruins. I wrote about this 200-year-old cemetery on Datha Island just two years ago, and there has been an exciting development since then. Synthesizing research done in the last two years with the ground-penetrating radar survey performed in 2005, I can confidently say that John Sams (1769-1798) is buried here on Datha. John was William and Elizabeth Sams’ third son. His two older brothers never married. John and his wife, Catherine Bridget (Deveaux) Sams, were the first to give William and Elizabeth grandchildren.

In addition, it looks like we may have found Edward Hext Sams in Jacksonville, Florida.

Many of you have been to the Sams Family Cemetery on Datha Island. It sits along the east side of Dataw Drive, about 100 yards northwest of B.B. Sams plantation complex tabby ruins. When the first person, William Sams, was buried here in 1798, there was no road where Dataw Drive is now. You would have docked down by Gleason’s Landing and taken a route closer to today’s Longfield Drive before turning east and heading over to the BB’s plantation house.

I’m speculating here, but the resting place for William Sams (1741 – 1798) was likely selected by him and his wife Elizabeth (Hext) Sams (1746 – 1813) some years before William died. The cemetery oak, which is standing majestically there today, would have been impressive even back then. Experts in 1984 gauged its age as “Possibly more than 400 years old…” A cleared area under this majestic tree would have made for a lovely location. His wife Elizabeth joined him there in eternal rest 15 years later.

In 1813, when Elizabeth (Hext) Sams died, the cemetery consisted of at least two graves under the oak tree, William and Elizabeth. However, recent research leads me to believe there may have been two other family members that preceded Elizabeth in death; her sons, Robert and John.

Robert died unmarried about 1790. All four of the Wadmalaw-born sons came to Datha when their parents bought the island in 1783. He would have been in his mid-20s at his death, and there is no evidence of a Sams family cemetery up in Wadmalaw.

Through Teresa Bridges’ diligent research, we know John was married in Beaufort and died in Beaufort, though he did spend time with a plantation up in Goose Creek. The exciting news is we have confirmation that he died in Beaufort in August of 1798, just seven months after his father, William. This begs the question, where is John buried? I’ll have more to say on this in a moment.

By 1820, four more graves were added to the Sams Family Cemetery. They included two young children of Lewis Reeves (1784 – 1856) and his wife Sarah (Fripp) Sams (1789 – 1825) and two children of Berners Barnwell Sams (1787 – 1855) and his wife Elizabeth Hann (Fripp) Sams (1795 – 1831).

It’s unclear when the tabby wall was built around the Sams Family cemetery. However, it is unlikely that William would have done this in the 1790s, long before any burials had taken place (though son Robert Sams may have been the first.) In 1832, Methodist ministers visited Datha Island on their mission through the sea islands of the Lowcountry. The wall most likely was added around 1833 when the chapel was built. By then, there were ten graves in the cemetery.

“As a result of the mission of 1832, the Sams brothers built a comfortable house of worship on Datha the following year.” [Rowland, page 356]

West of the orange orchard was our family burying ground. It was shaded all over by the spread of the largest live oak tree I ever saw. This tree grew in the middle of the graveyard, and threw its limbs out and around in all directions, even taking under its cover the wall which encircled the yard. On the east of the oak between it and the orange orchard, was a chapel, which was so placed as to form part of the wall, which ran around the whole spot.

Reverend James Julius Sams (1826 – 1918)

I believe it wasn’t just the missionaries that inspired the chapel. The year before they visited Datha, BB Sams’ wife died giving birth to their daughter Elizabeth Exima Sams (1831 – 1906). This would be hard on any family. The DHF did preservation work on the cemetery wall in 2006. The anticipation of this preservation is why a ground-penetrating radar survey was performed in 2005. Before I address that survey, let’s look at the layout of the graves in the cemetery.

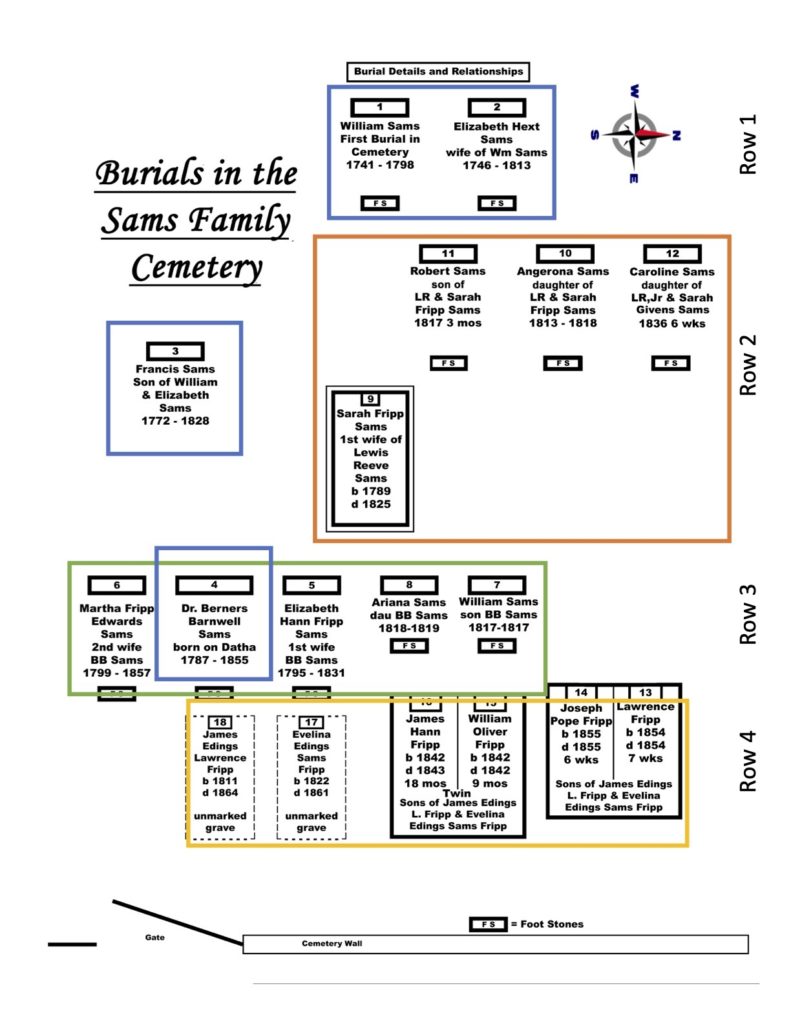

I took the liberty to add the family groupings identified by the colored boxes. Blue identifies William and Elizabeth Sams and their two sons. Orange is for Lewis Reeve Sams’ family members. Green is Berners Barnwell Sams and his family, and yellow is the J.E. Lawrence Fripp and Evelina Sams family. These groupings reveal insights into the intentional layout of the cemetery.

William and Elizabeth Sams are the oldest generations buried here, near the west wall. The others buried here are Berners Barnwell & Elizabeth’s son William (1817-1817) and Lewis Reeve & Sarah’s son Robert (1817-1817). These two burials in the late summer of 1817 established the Lewis Reeve & Berners Barnwell areas of the Sams family cemetery. They also secured the generational pattern to the graveyard.

Row one is William & Elizabeth, and I now believe their oldest son John Sams (1769-1798). Row two is for the oldest son on the island and his family (i.e., Lewis Reeve). Row 3 is for the other son on the island and his family (i.e., Berners Barnwell.) Finally, row four is for the grandchildren’s generation and beyond. The deaths in 1817 effectively set the cemetery’s architecture for generations to come. The last confirmed burial here was 1864.

There are some exceptions to this pattern. Francis Sams (1772-1828) was the last of the four Samses sons born on Wadmalaw Island, SC. He never married and has a headstone in row two, which makes sense. But the location of his actual grave is a bit of a mystery.

Caroline Sams (1836-1836) was a great-granddaughter of William and Elizabeth, the daughter of Dr. Lewis Reeve Sams, Jr. (1810 – 1888). Three Lewis Reeve Sams (Sr.) family members were already at rest on Datha by her death. Therefore, I believe it was a family decision to bury her near the others.

While this overview of the cemetery is interesting, what can be discovered below ground is essential to appreciate this hallowed ground fully.

Ground-Penetrating Radar

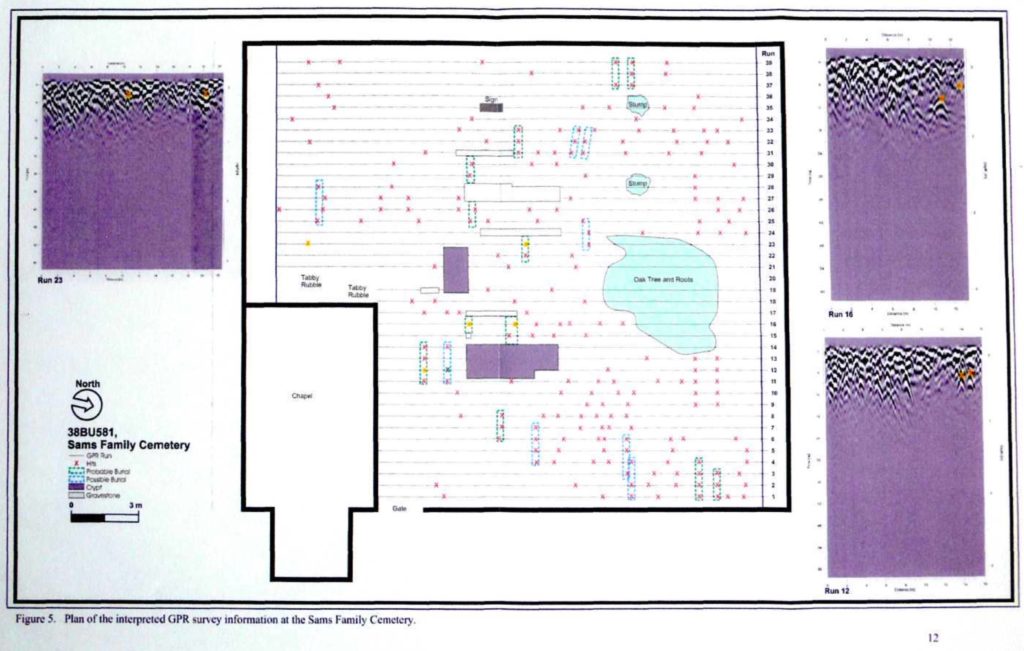

On 11 March 2005, a firm hired by the DHF performed a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey of the Sams Family Cemetery and several other locations. (The full report is linked in the sources below.) GPR is often used to survey old cemeteries for two primary reasons. First, they are non-invasive; no digging is involved. You roll a radar over the ground in precise transects and record the returns from radar pulses sent into the soil. The equipment looks like an electric lawnmower with a laptop computer attached.

Second, the radar image created of the top ten feet or so of the earth is quite precise. It reveals disturbances in the ground, both natural (e.g., big roots of trees and changes in soil composition) and man-made (e.g., graves.) A likely adult grave has radar hits of the same depth which form a line about 60 inches long. On the other hand, this type of survey technique is not perfect, especially when it comes to children’s graves from centuries ago. Also, some types of coffins or underground vaults can present challenges, because of unexpected radar returns. Let me give you an example.

The history of burials and coffins is dependent on many factors and varies around the world. In the U.S., before the Civil War, nearly everyone was buried in a wooden coffin. However, cast iron caskets with windows became available as early as the 1840s. Of course, their expense made them rare. We had a cemetery back in our community in Northern Virginia similar to the Sams Family Cemetery, but not nearly as old. We did a GPR survey of it and were surprised to find one particular gravesite from 1901 with a radar return like no other. It was like looking at the beam of a flashlight on the radar screen – a bright white large spot. The archaeologists knew what it was right away, though they were a bit startled too. The depth, shape, and size of the return confirmed it was a metal casket. It was quite a surprise to find an expensive metal casket used in what was then a small farming community. It says a lot about the woman buried there. Now back to Datha Island.

GPR Survey Results for Sams Family Cemetery

It takes unique expertise to interpret the GPR survey’s underground picture; note the three purple inserts in the diagram above. Another challenge comes when comparing the under-ground image to the above-ground view with the set of headstones and footstones you can see. The above figure shows both. Graves don’t move, but monuments do. Some gravestones in the above image do not appear to have corresponding graves under them. Monuments get moved and buried intentionally to protect them. Foot-stones get carried away for whatever reason, maybe just as a souvenir. In any case, memorials are not always put back in the correct location (i.e., over the grave.)

This survey scientifically determined the location of between 19 and 26 graves. Above ground, we have 16 engraved headstones (more on that in a moment.) A good percentage of the 19 to 26 grave locations are associated with the headstones, though we could not look under the crypts with the radar equipment. However, it’s safe to assume in this particular cemetery that none of the headstones are cenotaphs. In other words, none of the monuments commemorate a person buried elsewhere, as often happens with wartime deaths. However, it does appear that the headstone for Francis Sams is not over his grave. I believe his actual grave is one of those found in the northwest quadrant of the cemetery. This still leaves us with five to ten graves without names.

The earlier diagram above shows 16 headstones plus two confirmed graves (yellow box). The graves next to (i.e., south of) the four children in/under the crypts in row four do not have headstones. However, we have reliable evidence that tells us the parents were buried there. The GPR survey revealed two graves just to the south of the children. JEL Fripp and his wife Evelina are buried right where we expected.

This brings me back to the original question – who else is buried in the Sams Family cemetery? One remote possibility is that a few (enslaved) household servants were buried in the Sams Family cemetery. We have no record of this happening, but we’ve heard it happening in Beaufort County.

It’s more probable that other Sams’ family members are buried here. Given that there are no known headstones and burial locations for four of the seven sons of William and Elizabeth Sams, I looked at them first.

Robert Sams (1764 -before 1790) – burial site unknown.

Robert was the oldest son of William and Elizabeth Sams. He died unmarried and without issue (i.e., no children.) Robert is named after his grandfather Captain Robert Sams (1706 – 1760), who spent a lifetime on Wadmalaw Island, though he did own 500 acres on Hilton Head Island. Records for this son are very slim. When William and Elizabeth moved to Beaufort in 1783, Robert was old enough to stay behind on Wadmalaw, though I don’t know if he did. This would be interesting if we ever uncover evidence that he is buried in the Sams Family cemetery. It would push the cemetery’s age back nearly a decade and confirm in my mind that the cemetery location was picked by William and Elizabeth Sams long before William died.

William Sams, Jr. (1766 – 1817) – burial site probably on Datha.

We have multiple reports that William lived in Beaufort later in life and died here. Because he never married, we have no other family to help resolve his burial location. Although William died before Rev. James Julius Sams was born, JJ mentions “Uncle William” in his memoir in the context of Datha Island. Also, the most authoritative compilation of Sams Family records was published by Lula Sams Bond in 1963. She says William is buried here. Fifty years earlier, Conway Whittle Sams (1864 – 1935) said the same thing in his unpublished family history. I conclude William is probably buried in the Sams Family cemetery in one of the unmarked graves found in the northwest quadrant. His brother Francis, who died in 1828, was probably buried near William.

John Sams (1769 – 1798) – burial site on Datha.

We have confirmation that John came to Datha with his parents when they bought the island in 1783. He was married in Beaufort in 1792 and spent a short time in the Goose Creek area north of Charleston in 1795. Soon after, he and his wife Catherine B. DeVeaux (1776 – 1829) returned to Beaufort. We now have documents showing John died in Beaufort shortly after his father in August 1798. Catharine remarried Dr. James Perry in Beaufort on March 1, 1803. [Bridges] Combined with the GPR results, I believe John Sams is buried on Datha next to his parents and his wife in an unmarked grave.

Edward Hext Sams (1790 – about 1845) – burial site probably in Jacksonville, Florida.

We know Edward went to McIntosh County, Georgia, in the 1810s with his brothers William and Francis with ambitions to start their plantations [Rev Walter Birt Sams.] That went well enough for Edward to return to Beaufort to marry Sarah Emily Fripp (1794 – 1837) in 1814. In the 1830 and 1840 Census records in Duval County, Florida Territory, he appears some years later. Additional research shows that some of his children ended up in Charleston, SC, around 1850. Recently, a descendant of Edward Hext Sams stated that Dr. F. Sams (Edward & Sarah’s oldest son) was buried near his father and mother in the Old Jacksonville Cemetery.

I cannot (yet) account for many of the graves discovered in 2005 by the Sams Family cemetery GPR survey. Given the chaos here during the Civil War, maybe some clandestine burials occurred that we will never be able to confirm.

The gravestones are like rows of books bearing the names of those whose names have been blotted from the pages of life; who have been forgotten elsewhere but are remembered here.

― Fear Nothing

Sources

Bond, Lula Sams and Sanders, Laura Sams – The Sams Family of South Carolina, South Carolina Historical Magazine, January and April, 1963. [Link to PDF]

Bridges, Teresa (Winters) – Discussions between Teresa and Bill Riski from 2021 to 2022.

Holden, Joel and Riski, Bill – Family Tree for Sams of Dataw Island, Ancestry dot com, accessed 30 November 2020.

Poplin, Eric C., et al – Recent Archaeological Investigations on Dataw Island, Beaufort County, South Carolina. Prepared for The Dataw Historical Foundation Dataw Island, South Carolina – by Eric C. Poplin, Ph.d. (RPA Principal Investigator), Gwendolyn Burns (GPR Specialist), Andrew Agha (Archaeologist), and Brockington and Associates, Inc. – February 2006. [Link to PDF]

Rowland, Lawrence S., Moore, Alexander, Rogers Jr., George C. – The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina, Volume I, 1514 – 1861, 1996

Sams, Conway Whittle – History of the Sams and Whittle Families, circa 1905, unpublished.

Sams, Reverend James Julius – DATHA, undated, but believed to be written for his nephew Conway Whittle Sams, circa 1905 [Link to PDF]

Sams, Reverend Walter Birt – A History of Saint Andrew’s Episcopal Church, Darien, McIntosh Cty, GA from 1841-1993, published 1993.

Wenzell, Ron – Developers try to save historic 67-foot tree, The State, Columbia, South Carolina, 12 Aug 1984 [Link to PDF]

#52Sams Week 48 – Sams Family Cemetery

Other sources recommended by the Dataw Historic Foundation.

WELCOME TO DATAW ISLAND – Historical charm. Natural beauty. Extraordinary living.

HISTORIC BEAUFORT FOUNDATION – Preserving Beaufort’s Past for the Future