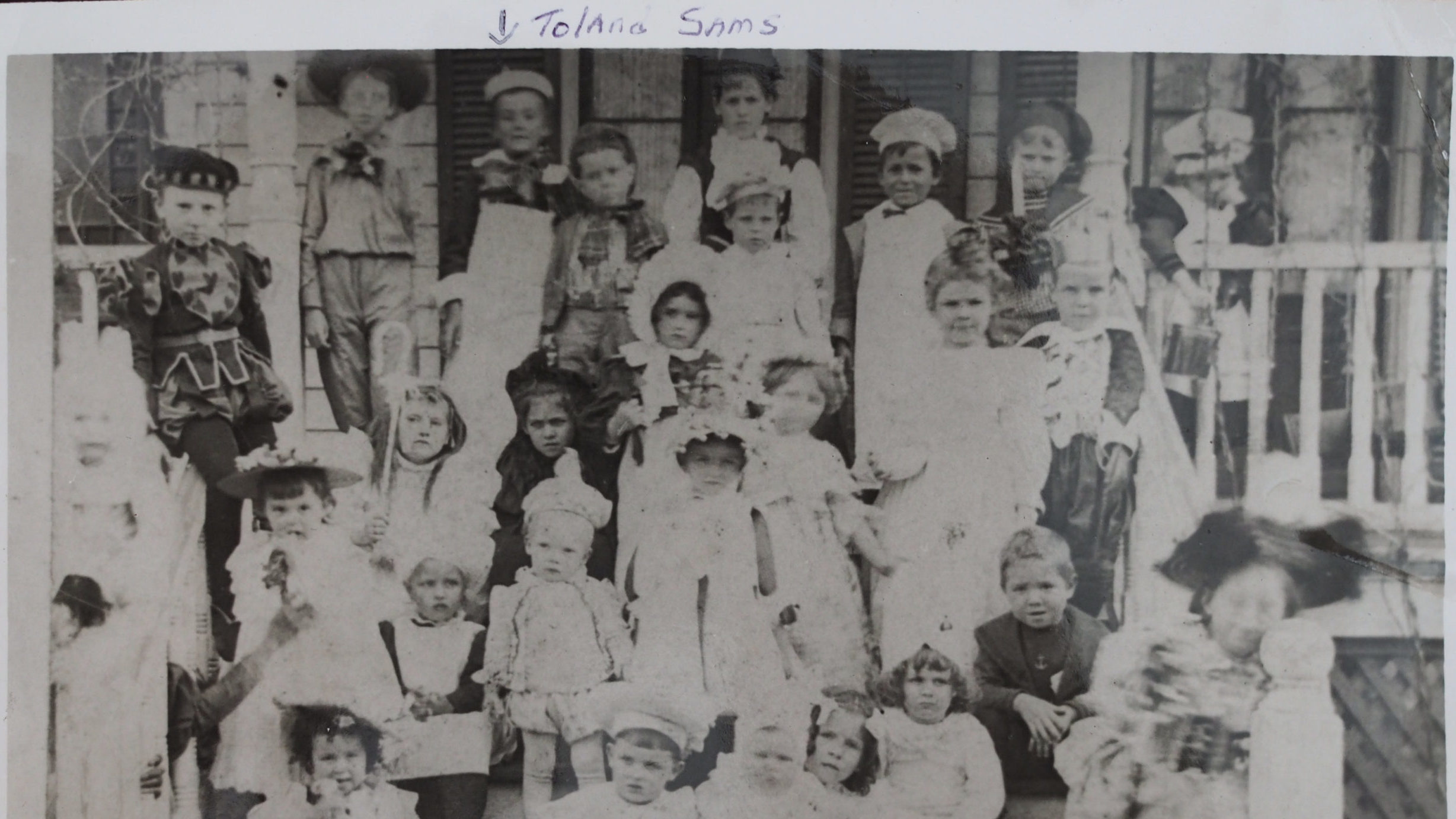

Birthday Party hosted by Mrs. Sydney Mills, Beaufort, SC. Both Melvin Toland Sams and Julian Sams in attendance. Circa 1895. Original photo from Ting Sams Colquhoun.

[Updated 19 December 2020]

This week is about what NAMES can reveal. As an amateur genealogist, I know that names can provide clues to a person’s past but can also present a brick wall. Discovering the ancestors of William Artman Riski is much easier than John Smith. Sometimes a naming pattern can provide us leads that we might otherwise overlook. This week I investigated the names of the seven sons born to William and Elizabeth Sams and found several surprises, including a British tradition.

British Naming Pattern

In her book, “In Search of Your British and Irish Roots,” Angus Baxter describes a pattern that was popular in England in the 1700-1875 period. Those years include three generations of Sams, from William and Elizabeth through their grandchildren. Since we know nearly all their ancestral lines originated in England, I thought it would be interesting to see if this widely accepted British pattern applied to the Sams.

- The first son was named after the father’s father

- The second son was named after the mother’s father

- The third son was named after the father

- The fourth son was named after the father’s eldest brother

- The first daughter after the mother’s mother

- The second daughter after the father’s mother

- The third daughter after the mother

- The fourth daughter after the mother’s eldest sister

This week I’m only going to address the first Sams generation starting with William and Elizabeth. I was curious if they followed this British naming pattern.

Using the above pattern for sons (they had no daughters), the facts are:

|

British Convention |

If pattern was followed, then son would be named |

Actual names given to sons are |

|

The first son would be named after William’s father |

Robert |

Robert |

|

The second son was named after Elizabeth’s father |

Francis |

William |

|

The third son was named after William |

William |

John |

|

The fourth son was named after William’s eldest brother |

John |

Francis |

There are several interesting points revealed in this table. First, the naming of their four oldest sons did honor the suggested relatives. You can see that all the names in the middle column appear somewhere in the last column. Second, they did not follow the sequence in the British naming pattern. The names in the last column are in a different sequence than the middle column.

They named their first four sons after the paternal and maternal grandfathers (Robert & Francis), the father (William), and William’s oldest brother John. Since they used the four suggested names that the British tradition suggested, they honored the four ancestors. I do not know why they named their sons in a different sequence than the British tradition suggests.

These first four sons were born between 1764 and 1772. There then is a ten-year gap during the American Revolution. After the war and their move to Datha Island in 1783, their family continued to grow. The next three sons are born between 1784 and 1790.

What is very curious is this. The first four sons had no middle names, while the last three did. The fifth son was Lewis Reeve Sams, the sixth Berners Barnwell Sams, and the seven Edward Hext Sams. Why they started giving their children middle names, I don’t know. There are at least two possibilities: religion or familial.

A recent article in Reader’s Digest says, “The way we use middle names today originated in the Middle Ages when Europeans couldn’t decide between giving their child a family name or the name of a saint. They eventually settled on naming their children with the given name first, baptismal name second, and surname third. The tradition was spread to America as people started to immigrate overseas.” [Cutolo] It’s apparent none of the Sams sons had middle/baptismal names based on saints. The first four boys had no middle name. As for the last three sons, here’s their story.

Lewis Reeve Sams

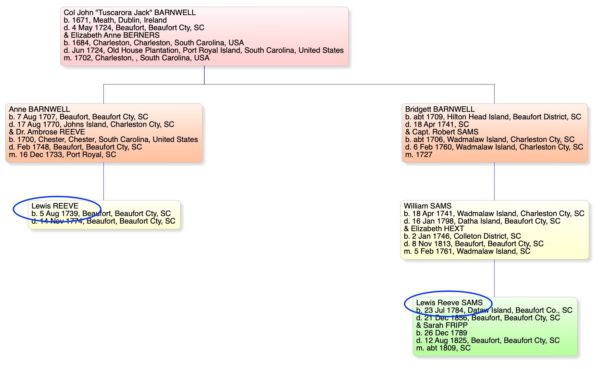

Lewis most certainly is named after William Sams’ cousin on his mother’s side. Cousin Lewis Reeve was one of only four children of Willam’s aunt, Anne Barnwell. All four were born to Anne and Dr. Ambrose Reeve (she had three other husbands!) Their only other son, Thomas, died in infancy.

Lewis Reeve Sams was born soon after they moved to the Beaufort area. Lewis Reeve, William’s cousin, had deep roots in Beaufort. It’s as if William and Elizabeth were saying to their family, and we are here in Beaufort to stay.

This chart shows how these two “Lewis Reeve”s are related.

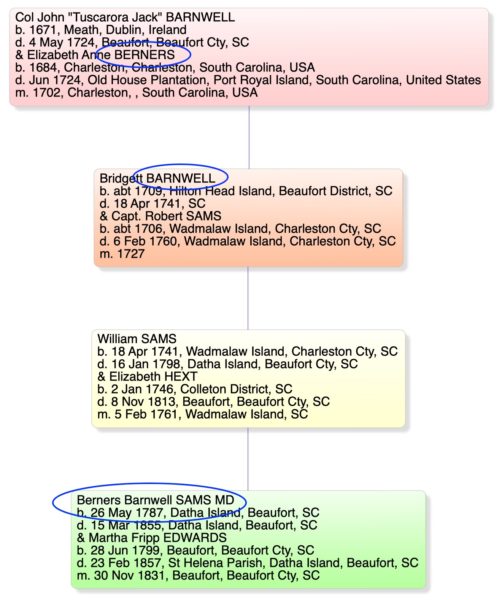

Berners Barnwell Sams

The sixth son of Wm & Elizabeth gets his first name from his great grandmother, Elizabeth Anne Berners (1684 – 1724), wife of Tuscarora Jack Barnwell. He gets his middle name from his grandmother, Bridgett Barnwell (1709-1841), wife of Capt Robert Sams (1706 – 1760).

Berners as a surname dates back hundreds of years in England. Barnwell is as old, but with an Irish mix. Barnwells moved to Ireland in the 12th Century.

This son’s relationship to his namesake relatives is very direct, as shown below.

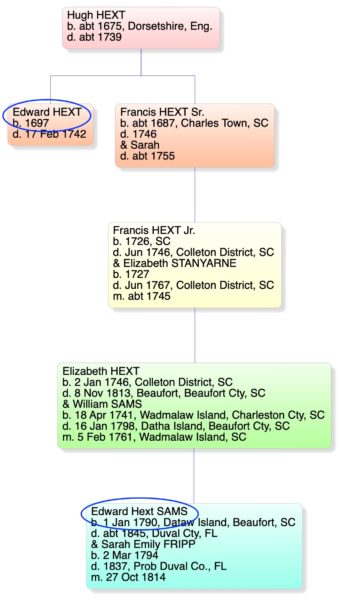

Edward Hext Sams

The seventh, and last, son of William and Elizabeth Sams was named after his mother’s great uncle Edward Hext (1697 – 1742). He gets his middle name from his mother’s maiden name, Hext. The Hext’s had deep roots in Beaufort. They were here long before William and Elizabeth moved to the area. I have a land record showing a Hext ancestor owning a plot in Beaufort before 1759. Edward could have gotten his first name from someone else, but I could find no other “Edward” anywhere in the Sams or Hext ancestral lines. We know little about the first Edward Hext, he died before Elizabeth was born. It’s not clear why she chose to honor her last son this way. I will note, she had already used the name Francis for her fourth son, so going with Francis Hext, her father, was out of the question.

Hext, as a surname, is also of British origin. In Old English, the word “hext” means “tall.”

This chart shows how these two “Edward Hext”s are related.

William and Elizabeth did not name any of their boys in honor of Elizabeth’s mother (maiden name Stanyarne) or Elizabeth’s half-sister (maiden name Nichols). They could have used these as middle names with the older sons but did not. Even when they began giving middle names to the younger Datha sons, it’s clear their motivation was not religious but familial.

One last point. It is relatively common in the south for both men and women to go by their middle, rather than first, name. I looked at several contemporary reports and Federal Census records from the period (i.e., 19th century.) Recently I received copies of the 1824 St Helena Parish tax returns for Lewis R. Sams and Berners B. Sams. They confirm that ‘our’ two planters used their first names in formal documents; brother Edward H. Sams probably did too.

It appears this first generation of Sams men born in Beaufort did not use their middle names in communications. This is decidedly not the case in the generation after them, but I’ll leave that for another day.

So there you have it. William and Elizabeth generally followed the British naming pattern for their sons. Why the first four were not given middle names when the last three were is curious. Does anyone have any ideas?

Epilogue

In Week 9, I wrote about the disasters faced by one southern family. James Edings Lawrence Fripp (1816 – 1864) and his wife Evelina Edings Sams (1822 – 1861) lost many of their children. In an epilogue there, I mentioned the mystery of who J.E. Lawrence Fripp’s parents were. Based on the research done this week, I feel even more confident that the middle names they gave their sons solve the mystery. His parents were James T.E. Fripp and Ann Pope.

Sources

Baxter, Angus – In Search of Your British & Irish Roots, 1982

Cutolo, Morgan – Why Do We Have Middle Names?, Reader’s Digest, 4 March 2020

Holden, Joel and Riski, Bill – The Sams Family Tree, Ancestry.com, accessed 16 Aug 2020

House of Names dot com – accessed 17 Aug 2020

Przecha , Donna – The Importance of Names and Naming Patterns

Rosengarten, Theodore –Tombee: Portrait of a Cotton Planter, 1986

#52Sams Week 33 – What’s in a Name

[print_posts post=”” pdf=”yes” print=”yes” word=”yes”]