The Marquis de La Fayette (1757-1834), a towering figure in both the American and French Revolutions, was a champion of liberty who left an indelible mark on history. La Fayette’s steadfast commitment to freedom and equality drove him to fight for these ideals on both sides of the Atlantic. His role in the 1781 Siege of Yorktown, which secured American independence, is legendary. Lafayette (common American spelling) later played significant roles in the French Revolution and the July Revolution of 1830, cementing his legacy as a leader who fought for human liberty.

In recognition of Lafayette’s contributions, the Maryland General Assembly passed a resolution on December 28, 1784, declaring Lafayette and his male heirs “natural-born Citizens” of the state. This effectively granted Lafayette honorary U.S. citizenship, a rare distinction that Congress reaffirmed in 2002. It demonstrated America’s enduring admiration for the man who helped secure its freedom.

Gilbert du Motier

Marquis de La Fayette

(b1757 – d1834)

Adrienne de Noailles

Marquise de La Fayette

(b1759 – 1807)

Why Go to America?

Born in 1757 to a wealthy landowning family in Chavaniac, Auvergne, Lafayette inherited both privilege and a strong sense of duty to champion justice. His lineage was steeped in military tradition—a “warrior-aristocrat” heritage that traced back to an ancestor who fought alongside Joan of Arc at the Siege of Orléans in 1429. Commissioned as an officer at 13, Lafayette embraced his family’s martial legacy, yet the ideals of the Enlightenment equally shaped his worldview.

The Marquis de Lafayette believed the American colonists were fighting for the same ideals of liberty and equality that he had felt deeply his whole life. He saw in the American Revolution a noble cause that resonated with his desire to fight for a society based on merit rather than social status.

As author Mike Duncan has aptly summarized, Lafayette’s decision to fight in America was not only about aiding the colonies but also about fulfilling a personal sense of destiny. Duncan likens this to the fictional character Lt. Dan Taylor in the movie Forrest Gump, who believed he was destined to die heroically in battle, only to be saved by Forrest Gump. Similarly, Lafayette’s life was driven by a belief in military duty and honor, and like Lt. Dan, he experienced moments of frustration but remained committed to the cause.

Lafayette’s Arrival in America

Lafayette landed near Georgetown, South Carolina, on June 13, 1777, before traveling overland to Philadelphia. His initial reception by the Continental Congress was lukewarm—Congress had grown tired of the many French mercenaries seeking fame and fortune in the colonies. However, Lafayette distinguished himself by offering to serve without pay and cover his expenses. This gesture, coupled with an endorsement from Benjamin Franklin, led Congress to accept him into the Continental Army.

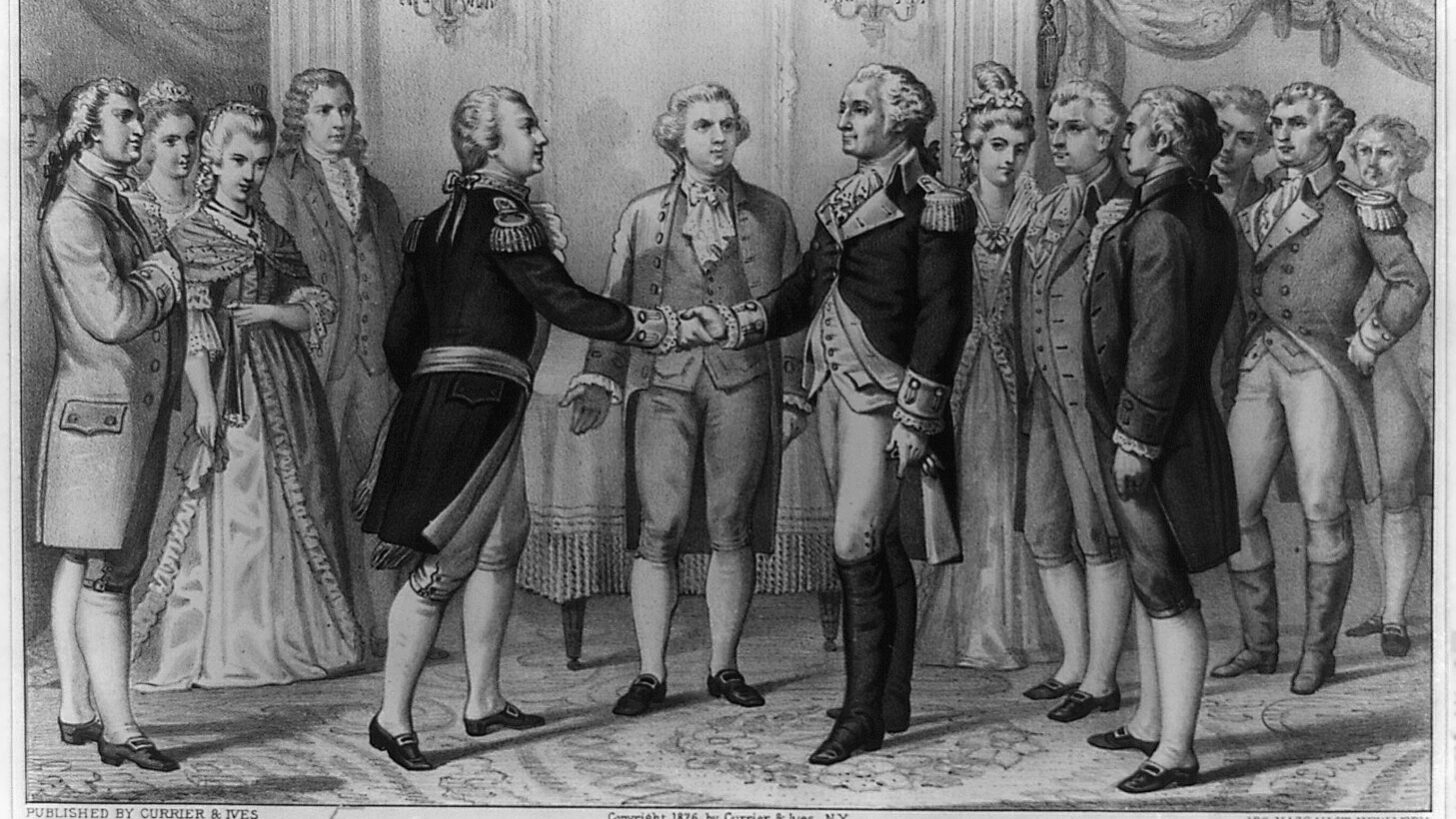

Lafayette’s introduction to General George Washington on August 3, 1777 (see featured image at the top) would change the course of his life. The two men quickly developed a father-son relationship, and Washington became a mentor to the young French officer. Lafayette’s loyalty was such that he later named his only son George Washington Lafayette.

Lafayette’s humility endeared him to the Continental Army. Upon joining Washington’s staff, he famously remarked, “I have come to learn, not to teach.” At 19, Lafayette was made a major general, a rank granted to many foreign volunteers, though it came with few actual command responsibilities. Lafayette, however, was determined to prove his worth on the battlefield.

His moment came during the Battle of Brandywine in September 1777, where he was wounded but refused to leave the field. He organized an orderly retreat and won the respect of his fellow officers. His performance earned him a command in later battles, including the Siege of Yorktown, where he helped secure Cornwallis’s surrender.

In a letter to Henry Laurens, President of Congress, Lafayette expressed the depth of his commitment:

The moment I heard of America, I loved her; the moment I knew she was fighting for freedom, I burnt with a desire of bleeding for her; and the moment I shall be able to serve her, at any time, or in any part of the world, will be the happiest of my life.

Marquis de Lafayette

(Camp near Warren, R.I., September 23, 1778)

Lafayette and the Sams Family

Lafayette’s arrival in 1777 placed him in proximity to William Sams and his family, who lived south of Charleston on Wadmalaw Island. While there is no direct evidence of contact, the significance of a French officer’s arrival would have been widely known in the area, especially given the role South Carolina would soon play in the Revolution. South Carolina saw more battles and skirmishes during the Revolution than any other colony, with over 200 engagements. By the time the Sams family relocated to the Beaufort/Datha Island area in 1782, they would have been well aware of Lafayette’s exploits and the growing importance of the French alliance.

Personal Sacrifice for Freedom

Lafayette’s involvement in the American Revolution came at a personal cost. While he fought on the front lines, his wife, Adrienne de Noailles, Marquise de La Fayette, remained in France, managing the family’s estates and raising their four children. During the chaos of the French Revolution, Adrienne and their family faced imprisonment and exile. In 1795, she was imprisoned and escaped execution during the Reign of Terror, thanks to the intervention of Elizabeth Monroe, the wife of U.S. envoy James Monroe. The Monroes’ close friendship with Lafayette, forged during the American Revolution, played a pivotal role in saving her life.

After the American Revolution, Lafayette returned to France, where he continued to fight for the principles of liberty. He was crucial in the French Revolution of 1789 and the July Revolution of 1830. However, his efforts to navigate the volatile political landscape in France often resulted in personal suffering. The entire Lafayette family endured periods of imprisonment and exile.

Lafayette’s Return to America as The Nation’s Guest

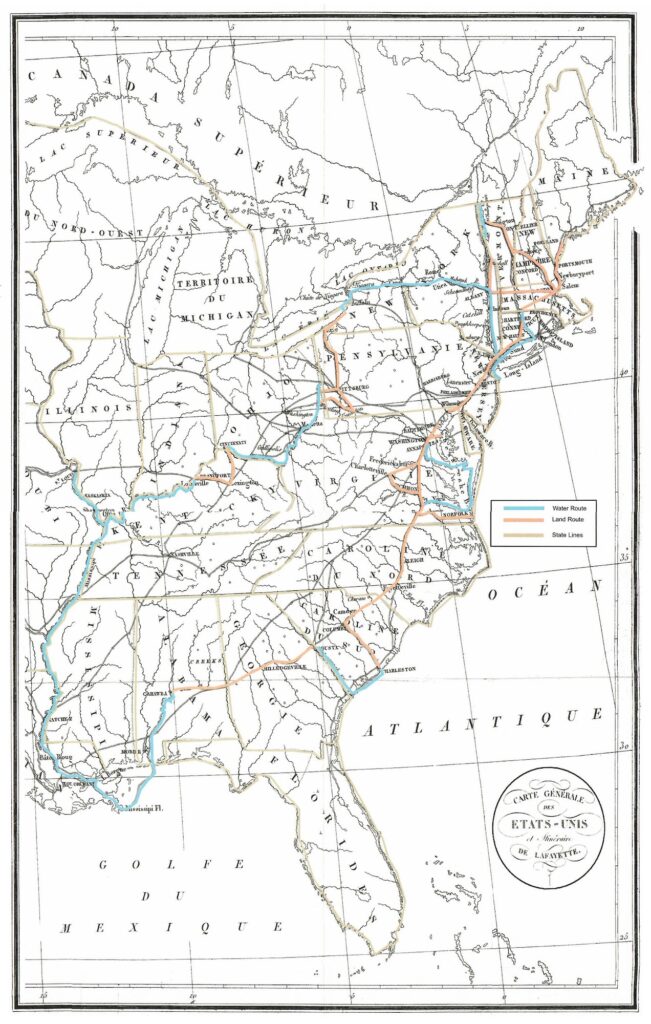

In 1824, fifty years after the American Revolution, Lafayette was invited back to the United States as “The Nation’s Guest.” His arrival was momentous, especially as many of the Revolution’s founding figures had passed away. His tour of the United States spanned 13 months and 6,000 miles, covering 24 states. Lafayette was celebrated as a living link to the Revolution, and his visit reignited national pride at a time when the young republic was still grappling with its post-war identity.

Lafayette’s 1824 tour of the United States was more than a nostalgic trip. As the last surviving major general of the American Revolution, Lafayette’s visit allowed the nation to express its gratitude. At the same time, President Monroe saw the visit as a strategic move to rally support for his Monroe Doctrine, which aimed to curb European influence in the Americas. The visit was also an opportunity for Lafayette to reconnect with old friends and restore his political standing in France, where he had recently suffered setbacks in his career.

The tour was grueling, but Lafayette was welcomed with open arms everywhere he went. By the time he reached Beaufort, South Carolina, in March 1825, William and Elizabeth Sams had passed, but their sons, Lewis Reeve Sams and Berners Barnwell Sams, would have been keenly aware of the significance of his visit.

In the map below, you can trace Lafayette’s arrival by land in Charleston. He then traveled by water to Beaufort and up to Augusta before continuing by land west across Georgia.

Lasting Legacy

Lafayette’s influence is still felt in America today. Sixteen counties and 21 cities in the United States bear his name, as do countless parks, schools, streets, and even mountains. Over fifty years, from the 1780s to the 1830s, Lafayette fought for liberty on both sides of the Atlantic. His legacy as a soldier, statesman, philanthropist, abolitionist, and idealist continues to inspire.

The Marquis de Lafayette is believed to have expressed deep regret over the persistence of slavery in the United States. While the following quote, frequently attributed to him, cannot be fully verified, it echoes his well-documented stance against slavery. Lafayette was a vocal advocate for gradual emancipation, though his influence on leaders like George Washington did not result in immediate policy shifts. Despite this, his convictions remained steadfast, and he is said to have remarked:

I would never have drawn my sword in the cause of America if I could have conceived that thereby I was founding a land of slavery.

Marquis de Lafayette

As Beaufort prepares to commemorate the bicentennial of Lafayette’s visit, the city will honor his legacy with events and celebrations. Lafayette’s remarkable life, defined by an unshakable devotion to liberty, inspires a world striving to uphold those ideals. Few historical figures rival the revolutionary impact of the Marquis de Lafayette—a hero whose influence transcends time and place.

Recommended reading

Hero of Two Worlds: The Marquis de Lafayette in the Age of Revolution by Mike Duncan, 2021

The Politics of Liberty in the Old World and the New: Lafayette’s Return to America in 1824 by Sylvia Neely, 1986

Lafayette and Slavery, by Hank Parfitt, President of the Lafayette Society.

Serpent in Eden, by Tyson Reeder, 2024